For all of human history, we have been plagued by viruses, with some of the most catastrophic epidemics stemming from the likes of:

Smallpox (Variola vera)

Measles (Morbillivirus measles)

SARS (A Coronavirus)

Yellow fever (A Flavivirus)

Zika (A Flavivirus)

Influenza (A and B)

The Dark History Of Influenza

Some of the most severe epidemics the world has ever seen was the result of the influenza virus.

This virus has the ability to change and mutate frequently during replication, dramatically increasing the chances of mutating into something especially deadly.

Major Influnza Outbreaks Over the Past 100 Years

| Outbreak Common Name | Strain | Year(s) | Death Toll |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Spanish Flu | H1N1 | 1918 | 90,000,000 |

| Asian Flu | H2N2 | 1957 | 698,000 |

| Hong Kong Flu | H3N2 | 1968 | 4,000,000 |

| Swine Flu | H1N1 | 2009 | 575,000 |

4 Major Influenza Epidemics In 100 Years

Over the years, there have been 4 major influenza outbreaks.

In 1918, nearing the end of World War II the Spanish flu affected nearly 1 third of the entire population of earth, killing about 6% of the population.

30 years later another flu known as the Asian flu killed between 1 and 2 million people.

10 years later it was followed by the Hong Kong Flu which killed 1-4 million and the Swine flu in 2009 killing 200 000 but affecting as much as 60 million people around the world.

Influenza has always been, and will likely continue to be a major threat to human life. The ability for these viruses to mutate, jump species, and resist medications is what has made it such a prevalent disease.

Every year we create new flu vaccines to target the "most likely" mutation of that year.

The truth is that these mutations are hard to predict effectively, because the species mutates so frequently. By the time we've created a vaccine, the virus has already mutated, often making that vaccine obsolete.

The 2009 Swine Flu Epidemic

After the 2009 global H1N1 pandemic, the CDC estimated the total number of deaths to be around 300 000 - 575 000.

The normal death toll is usually around 12,000 - 56,000 per year from influenza-related illness.

The rate of infection spread is incredibly fast

The Spanish Flu Epidemic Of 1918

The virus infected about a third of the population of earth, which meant about 500 million people were infected. By december of 1920, roughly 6% of the entire world's population had been wiped out by the virus. This accounts for about 90 million people. An estimated 80% of deaths were people under the age of 65.

In one year The Spanish Flu killed more than:

100 years of black death

24 years of HIV

4 years of world war (WW1)

The Spanish Flu

Severity Of The Worlds Most Catastrophic Events

New And Upcoming Virus’

Influenza A and B are segmented RNA viruses, which means they mutate often.

Frequent mutation increases the chances of developing new, deadly strains, or jumping species. It also makes it very hard to predict upcoming epidemic strains to protect the population.

H5N1 is of major concern because of its high mortality rate in the past (60%) and resistance to mainstream antiviral medications.

H7N9, H7N7, and H7N3 Bird flus are also of concern and some reports of human HA compatibility have been reported.

Source: Kaplan, M. and Webster R. (1977) 'The Epidemiology of Influenza', Scientific American Vol 237 (6), 88-106.

What Is Influenza?

Influenza is a group V varion (negative-sense single-stranded RNA genome)

It’s also a member of the Orthomyxoviridae family

(Enveloped viruses)

Other Group V Virion Species:

Ebola

Measels

Mumps

Rabies

Yellow fever

Marburg viruses

The Orthomyxoviridae Family

The Orthomyxoviridae family has a few different members, including influenza A, B, C, and another member known as Thogoto virus.

Naming Influenza: "H-N What?"

Influenza B and C are less common than influenza A, and there is far less variability with these species.

Influenza A is both common, and comes in an incredible amount of variability.

A naming system was developed to further categorize influenza A as a result. This is the H_N_ system most people are familiar with.

On every influenza A, there are 2 main protein complexes; hemaglutinin, and neuraminidase.

According to the CDC, there are currently about 18 different types of hemaglutinin, and 11 types of neuraminidase that can be presented on its surface.

Each of them have a corresponding number.

Therefore, H1N1 will have type 1 hemaglutinin, and type 1 neuraminidase.

H3N7 would be different, having type 3 hemaglutinin and type 7 neuraminidase.

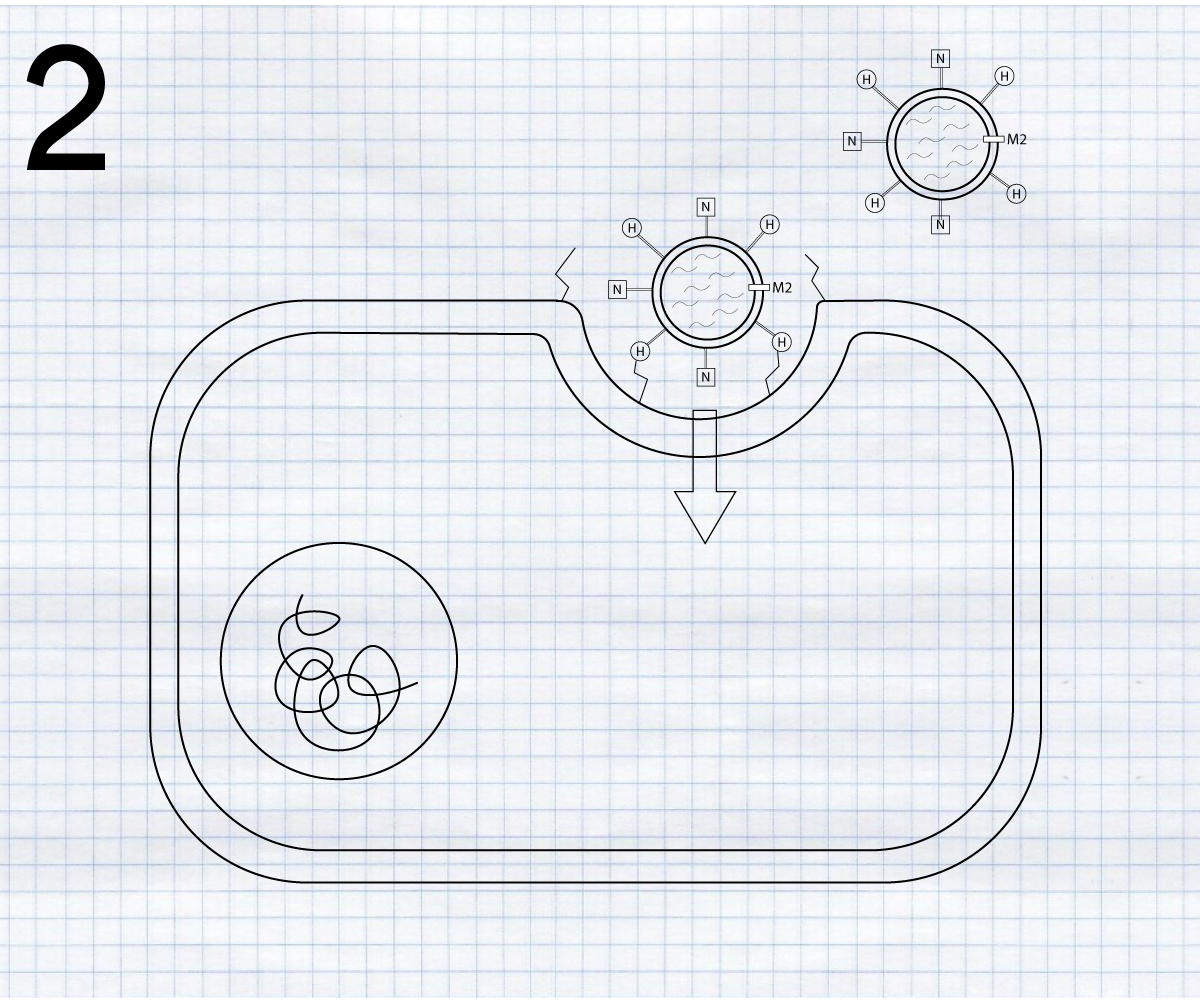

How Does The Influenza Virus Make Us Sick?

The virus uses hemaglutinin to bind to sialic acid on the cell membrane.

The virus enters the cell, contained inside a vacuole.

Lysosomes combine their contents with the encased virus.

The pH is reduced inside the vacuole, causing activation of the hemagglutinin spikes on the viral envelope.

Hemaglutinin changes structure and fuses the virus with the vacuole, dumping its contents (segments of RNA) into the cell.

Viral RNA hijacks the cells DNA to produce more viral proteins, which are then released into the cell and float outwards to the cell membrane.

These enzymes form new viruses using the cells own plasma membrane. Upon leaving the cell, hemagglutinin is bound to the sialic acid once again, stopping the newly formed virus from leaving.

Viral neuraminidase cleaves the sialic acid, allowing the virus to separate from the cell. It then goes on to infect another cell and perpetuate the process.

Further Reading:

Recent Blog Posts

References:

World Health Organisation. (2016). WHO | Influenza (Seasonal). Retrieved from: mediacentre/factsheets/fs211/en/

World Health Organisation. (2017). WHO | HIV/AIDS. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/gho/hiv/en/

CDC. (2012). First Global Estimates of 2009 H1N1 Pandemic Mortality Released by CDC-Led Collaboration | Spotlights (Flu) | CDC. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/flu/spotlights/pandemic-global-estimates.html

Britannica. (2017). World War I - Killed, wounded, and missing | 1914-1918 | Britannica.com. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/event/World-War-I/Killed-wounded-and-missing

Li, F., Ma, C., & Wang, J. (2015). Inhibitors targeting the influenza virus hemagglutinin. Current medicinal chemistry, 22(11), 1361-1382.

Murphy, F. A., Fauquet, C. M., Bishop, D. H., Ghabrial, S. A., Jarvis, A., Martelli, G. P., & Summers, M. D. (Eds.). (2012). Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses (Vol. 10). Springer Science & Business Media.

Wu, S., Huang, J., Gazzarrini, S., He, S., Chen, L., Li, J., ... & Liao, G. P. (2015). Isocyanides as Influenza A Virus Subtype H5N1 Wild‐Type M2 Channel Inhibitors. ChemMedChem, 10(11), 1837-1845.

As COVID-19 continues to spread around the world, we’re getting a lot of questions on what the potential role of herbal medicine is during the outbreak. Learn how the virus works and how to limit your chances of transmission.