The novel coronavirus responsible for COVID-19 (Sars-Cov-2) has been lighting up headlines around the world as it spread outward from China.

What are the treatments being used for the outbreak? Are there any plants researchers exploring as they search for new preventative measures and treatments?

In a matter of just a few weeks, outbreaks in countries like Italy, the United States, Iran, France, Spain, and more have all started to buckle under the pressure now placed on the healthcare system. Sick patients are turning up in ever-increasing numbers in need of intensive care.

Learn what official organizations such as the CDC and WHO are recommending to avoid the illness, how Sars-Cov-2 works, what measures are being explored to find treatment, and what you can do to further reduce your chances of contracting the virus.

We’ll also cover some of the most promising herbs being explored to help with the prevention and prognosis of Sars-Cov-2 infection.

Disclaimer: There is No Official Evidence To Support The Use Of Any Alternative Treatment For COVID-19

Every major media outlet on earth has been reporting non-stop about the new coronavirus sweeping across the planet.

Despite the incredible amount of attention the virus is getting from governments, media sources, and the public — there remains no clear treatment for the infection.

The information in this article should not replace the medical advice recommended by the CDC, WHO, and various other health organizations around the world working hard to develop effective treatments for the virus.

Herbal medicine is not an effective treatment for serious infectious diseases like COVID-19 — the only assured way of halting the spread of the virus is to avoid exposure. Practice social distancing, wash your hands often, and wear protective equipment.

Herbs alone won’t reduce the severity or chance of transmission of the virus but may play a role in maintaining a high level of health to help withstand the effects of the virus. The idea is that by using plant-based medicines and optimal nutrition, we may be able to strengthen weak points leveraged by the virus — primarily involving a disruption of the virus itself and bolstering the immune system and lungs.

A Cochrane Review investigating the results of alternative therapies used during the SARS epidemic suggested a combination of herbal and conventional medicine did not lower mortality rate, but concluded the combo may improve quality of life, reduce chances of deep lung infiltration, and a lower dose of medications like corticosteroids.

China is currently performing over 80 clinical trials on potential treatments for COVID-19 as well — including a few trials using traditional Chinese herbs.

With all of that aside, let’s get started.

How to Stay Informed on the COVID-19 Situation

There’s no shortage of reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic — but a lot of this reporting is spreading misinformation. While platforms like Twitter and Facebook are a good way to spread information quickly, you should always do your own fact-checking by following the official accounts of organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO), Centers for Disease Control (CDC), local government websites, and medical professionals specializing in epidemiology.

Here’s a list of the most credible sources to follow as the pandemic develops:

What is COVID-19?

COVID-19 is a disease caused by the virus Sars-Cov-2 — a newly discovered member of the Coronaviridae family of viruses. This is a large family of viruses infecting humans and other vertebrate species on every continent on earth.

Sars stands for severe, acute, respiratory syndrome — cov stands for coronavirus, and 2 refers to this virus being the second iteration of significance.

Some of the most severe cousins of Sars-Cov-2 are the Sars-Cov-1 virus (responsible for SARS) and Mers-Cov (Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome).

There are also a handful of coronaviruses that frequently sweep the globe each year during cold and flu season. Coronaviruses like 229E are among the most common causes of the common cold. Other viruses in the family include NL63 and HKU1. (Source: CDC Coronavirus Types).

Despite the similarities, Sars-Cov-2 is different from the common cold and substantially more dangerous. While the symptoms are similar (cough, runny nose, fatigue), the severity of the infection is dramatically higher.

The main symptom difference between the two is the high fever with COVID-19 and severe shortness of breath.

How the Coronavirus Makes Us Sick

The virus infects deep within the lungs. It hijacks and destroys cells that make up the region of the lungs where gas exchange occurs.

Infected cells lack the ability to produce biological surfactants that keep lung passages open.

The result of this is severe difficulties moving oxygen from the lungs to the blood.

But there’s another problem that makes this effect even more dangerous.

Recent research suggests the virus also interferes with blood production — causing the removal of heme from red blood cells. Heme is the part of the blood cell that allows it to transport oxygen (theoretical). [22].

This means the virus not only makes it harder to breath by attacking the lungs, it also attacks the red blood cells responsible for transporting oxygen around the body.

The result is a dramatic drop in blood oxygen levels. Cells around the body begin to starve for oxygen. The most severe cases of the condition (roughly 10% of the infected) require high-flow oxygen to stay alive.

This is especially dangerous for people with preexisting conditions affecting the red blood cells (such as anemia, diabetes, or leukemia).

The exact death rate of this particular virus is still being evaluated, but the WHO recently reported the virus to have a 3.4% death rate — and up to 14% in the most at-risk populations.

How the Wuhan Coronavirus Works

In order to understand what preventative measures or potential treatments to explore, we have to first understand how the virus works.

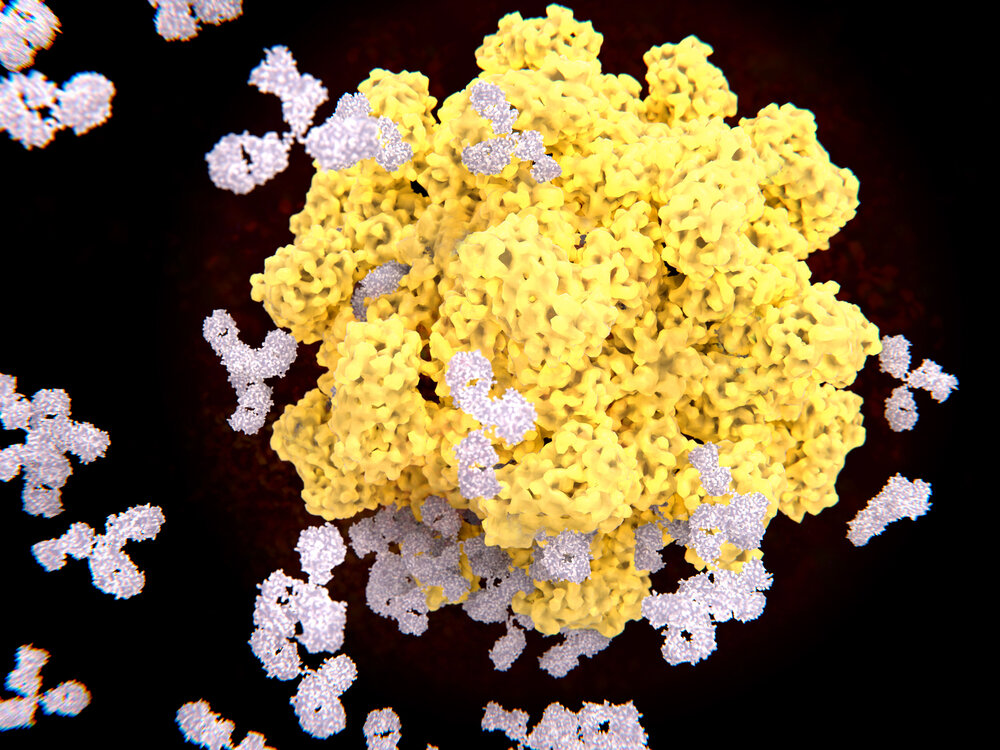

Coronaviruses are essentially made from a central DNA or RNA core surrounded in a protein and lipid shell (called an envelope). There really isn’t too much to them. Even the genome of these organisms is very simple — consisting of about 30,000 sequences. To put this in perspective, humans have over 3 billion.

The genome of the virus contains the information on how to hijack the target cells in the body and turn it into a factory to produce more copies of the virus.

Anatomy of Sars-Cov-2

The coronavirus gets its name from the crown-like appearance of the virus (corona essentially means “crown-like”). Large spikes protrude out from the viral envelope which consists of a combination of lipids and proteins.

These spikes are what allows the virus to enter the cells to infect them.

Let’s follow the step by step process the coronavirus follows to infect our cells:

Step 1: The Virus Enters the Body Contained in Tiny Water Droplets

Sars-Cov-2 is transmitted contained in water droplets. These droplets were formed in the lung tissues of infected people as they cough or sneeze. The virus can also transmit in the saliva or mucus of infected individuals.

We may inhale droplets containing the virus directly or transfer the virus into the body through the eyes, nose, or mouth after touching infected surfaces.

Once inside the body, the coronavirus makes it’s way towards the lungs.

Step 2: The Spikes On the Outside of the Virus Bind to Special Proteins In The Lungs & Fuse With the Cell Membrane

The large spikes of the coronavirus serve an important purpose — it holds the key to getting inside the target cells in the lungs.

The coronavirus will bind to a specific protein structure on certain lung cells called ACE2. Once bound to ACE2 it activates other components on the viral envelope that allow it to fuse with the cell.

Step 3: The Virus Releases its Payload Directly Into the Cell

As the virus begins to fuse with the cell, it eventually dumps the entire payload of viral RNA into the cell. These RNA molecules are the blueprints for creating new viruses.

The nucleus of our cells have special protein complexes that are designed to read RNA produced by the body in order to build new proteins. Viral RNA hijacks this system completely.

Step 5: The Infected RNA Read the RNA Snippets and Begin Assembling New Viral Proteins

Once the viral RNA reaches the nucleus of the cell it takes over and turns the nucleus into a virus-manufacturing facility. All normal cellular processes come to a halt as the viral RNA leads production.

Step 6: Viral Proteins Collect on the Outer Edges of the Cell and Bead-Off As Newly Formed Viruses

As viral proteins are assembled in the nucleus of the cell, they begin to float to the outside fo the cell along the membrane. They merge together and accumulate into new viral bodies, which eventually break free from the cell to go on and infect new cells.

Step 7: The Infected Cell Eventually Dies

As the infected cell continues to build new viruses instead of doing the job it’s supposed to, it will eventually wither and die — releasing millions of copies of the virus and triggering the immune system in the process.

Eventually the immune system will develop effective antibodies to attack and destroy the virus

The Search For Treatment Options

There are currently no effective treatment options for the virus, but there are a few areas currently being investigated. Researchers in Canada were able to isolate the virus which is an important step in identifying exactly how the virus works and potentially finding a cure.

Unfortunately, there are some concerns that the virus will continue to mutate faster than we can develop vaccines. So far the virus has already mutated roughly 30% since it’s discovery [23].

Current Areas of Treatment/Prevention Being Investigated:

1. Vaccination

A vaccination is currently being developed by several independent and government labs, but clinical trials for the first prototype vaccine isn’t estimated to begin until April or May 2020.

Companies Working on a Vaccine Include:

GlaxoSmithKline — Vaccine adjuvant System

Inovio Pharmaceuticals Inc. — DBA-based vaccine

Johnson & Johnson US

Moderna Inc — RNA-based vaccine

Sanofi

Medicago

There are also a few companies that have joined forces to try and find a vaccine together:

iBio and CC-Pharming — Plant-derived coronavirus vaccine

GeoVax and BravoVax — Based off GeoVax MVA-VLP vaccine

Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and GSK

CEPI and University of Queensland — Hoping to fast track vaccine development with molecular clamp technology

CEPI, Moderna and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases — RNA-based vaccine

2. Antivirals

There are currently no effective antivirals for treating COVID-19, but there are at least 9 pharmaceutical companies working on finding effective treatments:

Gilead Sciences Inc. — remdesivir

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. — No name (monoclonal antibodies)

Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd. — TAK-888 (hyperimmune globulins)

Vir Biotechnology Inc. — No name (monoclonal antibodies)

Takis and Evvivax — No name (antibodies)

Regeneron Pharmaceuticals and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services — Treatment based on VelociSuite® and VelocImmune®

There Remains No Effective Treatment for the Virus at this Time

Until an effective treatment is discovered, we’re forced to wait and keep infected patients stabilized. Treatments for the infected mainly involve fluid and oxygen therapy to keep the body in as stable a condition as possible.

Drugs are also used to maintain homeostasis, keep blood pressure and heart rate stable, and ease the pain and discomfort of the condition while the immune system does its best to fight off the virus.

Prevention is the Best Form of Treatment

This may sound super cliché, but it’s true. If we can limit our exposure to people who carry the virus and practice effective hand washing on a consistent basis, our chances of contracting the infection is substantially reduced.

Avoid Smoking

Recent evidence suggests smokers have much higher expressions of the protein ACE2 in the lungs — which gives the virus ample opportunity to attach itself and infect the cell. This could be one explanation of why men in China were more likely to experience the most severe symptoms of the disease (men in China are more likely to smoke than women).

It’s recommended that you avoid smoking anything, including marijuana or e-cigarettes — at least until the pandemic comes to an end.

What to Do if You Get Infected

Plant-Based Medicine & COVID-19: Insights & Data

So let’s get to the crux of this article. What (if any) herbs should we be looking at in terms of the Sars-Cov-2 virus?

While it’s important to remember that herbal medicine isn’t considered an effective prevention or treatment for the disease, it can add a layer of protection, along with adequate nutrition, exercise, and taking measures to avoid contact with the infection.

There are a few studies being done in China and other parts of the world to screen for plants and herbal formulations that could be active against the virus.

Herbs are a great starting place to find new, effective medicines. Roughly half of all pharmaceuticals today contain at least one plant-derived compound [17].

1. Herbal Antivirals: Coronaviridae

Herbal antivirals are best used in the early stages before infection takes place. They usually target protein structures on the viral envelopes that make it difficult for the virus to infect the cell.

A good example of this is a herb called elder (Sambucus nigra) which binds and disables proteins on the outside of the influenza virus that’s necessary for helping the virus leave an infected cell to infect more cells.

It’s likely there are other herbs (including elder) that could potentially inhibit the enzymes the coronavirus requires to gain access into our cells via the ACE2 protein.

While there’s virtually no information on COVID-19 specifically, we have a lot of information on potential plant species or extracts and their effects on related viruses like SARS, MERS, or 22E9.

Let’s explore what we know so far about herbal antivirals and coronaviruses.

A) Elder (Sambucus nigra)

Elder is rich in antiviral compounds including lignans, triterpenes, and caffeic acid which have been tested on a large number of different types of viruses (including coronaviruses). The herb has been shown to inhibit many viruses by interfering with the viral envelopes — rendering them non-infectious.

Elder has shown promise towards the following viruses:

Influenza A (various strains

Influenza B

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV)

Herpes simplex virus (HSV)

Tobacco mosaic virus (plant virus)

Mycoviruses (various)

Haemophilus influenzae

Coronavirus (in chickens)

Coronavirus NL63

One study, in particular, found a stem extract of the elder species Sambucus Formosana Nakai was able to strongly inhibit the replication of the coronavirus NL63 [8]. Researchers in the study attributed most of this effect to caffeic acid.

Another study found elder (Sambucus nigra) extract may inhibit Infectious Bronchitis Virus (a strain of pathogenic chicken coronavirus) if given at an early point of infection [9].

B) Bupleurum (Bupleurum falciform)

Bupleurum is high in a group of triterpene glycosides known as saikosaponins (A, B2, C, and D) were shown to exhibit direct antiviral activity against a related virus, HCoV-22E9 [2] — which is one of the main viruses responsible for the common cold.

In particular, saikosaponin B2 exhibited the strongest potency — especially if administered before the virus enters the host cells. This suggests saikosaponins work to interfere with early stages of viral replication, such as the penetration of the virus into the target cells.

Saikosaponins have also been shown to inhibit other viruses, including:

Other herbs with these compounds include Scrophularia scordonia and Heteromorpha spp. — both of which have a long history of use for viral infection.

C) Houttuynia cordata

Houttuynia is a herbaceous plant native of Southeast Asia. It has a unique “fishy” taste which makes it useful as a garnish and flavoring agent in some culinary dishes. It was also one of the main medicinal herb species used in China during the SARS outbreak. At the time of the outbreak, there was no available research to prove the herb was useful for fighting the infection and most of the people using the herb were going of traditional uses for the herb — which involved lung abscesses, phlegm, cough and shortness of breathe, pneumonia, and viral infection — all of which are relevant symptoms for SARS and COVID-19.

Five years after the SARS outbreak a study was published by the Chinese University of Hong Kong that highlighted the potential role houttuynia could play in coronavirus infections [10].

The study found the following effects of the herb:

Stimulates the proliferation of splenic lymphocytes — necessary immune cells for fighting infection

Increased the proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells — key components of the adaptive immune response necessary to fight viral infection

Increased the secretion of IL-2 and IL-10 — both of which are key immunoglobulins for fighting viral infection and are sometimes used as treatments in hospitals

Inhibited SARS-CoV 3C-like protease (3CLpro) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) [6] — key enzymes involved with the viruses function

D) Honorable Mentions

A Chinese screening analysis explored hundreds of Chinese herbs in search of species that could offer anti-SARS-CoV activity. The results highlighted the following species with clear inhibitory activity on the virus:

Isatis indigotica [3] — nsP13 helicase and 3CL protease inhibitor

Torreya nucifera [4] — nsP13 helicase and 3CL protease inhibitor

Lycoris radiata [5] — slows or prevents viral attachment and penetration

Artemisia annua [5] — slows or prevents viral attachment and penetration

Pyrrosia lingua [5] — slows or prevents viral attachment and penetration

Lindera aggregata [5] — slows or prevents viral attachment and penetration

Rosa nutkana [15] — shown to inhibit the activity of enteric coronavirus through unknown mechanisms

Amelanchier alnifolia [15] — shown to inhibit the activity of enteric coronavirus through unknown mechanisms

Hypericum perforatum [21] — inhibits (mRNA) expression in IBV (chicken coronavirus strain)

Isatis flowers

2. Herbal Immunomodulators & Lung Tonics

The next area of focus is on the immune cells located within lungs. The respiratory system is the primary target for coronaviruses — including Sars-Cov-2.

The idea is that supporting the health of the immune system in the lungs with herbs known to focus on this area of the body could limit the chances of contracting the disease. Strengthening the respiratory system could also limit the severity of symptoms if we do catch it.

This, of course, goes along with other measures like limiting exposure to irritants such as smoke or fumes.

Here are some of the most important respiratory herbs and immunomodulators to be aware of:

A) Mullein (Verbascum thapsus)

Traditional uses of mullein almost exclusively relate to the respiratory system. The flowers and leaves of the herb were used for their expectorant (removing mucus from the lungs) and demulcent (soothing effect) actions. It was used to treat conditions like bronchitis, dry cough, pneumonia, fever, tuberculosis, and asthma [16].

Mullein owes these effects to the high mucilage content of the leaves, which are a common ingredient in herbs that have an affinity for the respiratory tract. The herb also contains antiviral agents that have been shown to be effective against influenza [14] and herpes simplex [15].

Active ingredients like verbascoside may also reduce inflammation during respiratory infection [18]

Mullein is usually used in the form of a tea or tincture. Traditional methods of using the herb involved smoking it – but this isn’t recommended.

B) Astragalus (Astragalus membranaceous)

Astragalus is a member of the pea family of plants (Leguminosae). It has a long history of use as a lung tonic in China — where it’s known as huáng qí. Here, the herb is used as a preventative measure against lung infections of bacterial and viral nature.

This herb offers two main benefits towards lung infection which are relevant for Sars-Cov-2 infection:

Antiviral effects — polysaccharides from astragalus were shown to possess antiviral activity against a variety of enveloped viruses [19]

Immunomodulatory effects — astragalus extracts were shown to increase the number of lymphocytes and proportion of CD4+ lymphocytes [20]

Traditional use suggests taking the herb before developing a lung infection. Once symptoms of infection appear, stop taking the herb.

C) Other Immunomodulatory Herbs

Immunomodulators are compounds or herbs that support the activity of the immune system — including the production of immune cells, detection of antigens, and the elimination of infectious agents. This class of compound isn’t limited to stimulation of the immune system, but for limiting the severity of immune response as well.

There are a lot of immunomodulatory herbs available, each with slight differences in their target cells. Most immunomodulators have an effect on T abd B lymphocytes — as well as immunogolbulins such as IL-2, IL-6, IL-10.

These herbs are best used as a preventative action against infection rather than as a treatment.

Some of the best immunomodulating herbs include:

Reishi (Ganoderma lucidum)

Echinaceae (Echinaceae purpurea)

Garlic (Allium sativa)

Licorice (Glycyrhiza glabra)

Codonopsis (Codonopsis pilosula)

Reishi mushrooms (Ganoderma lucidum)

D) Respiratory System Herbs

(Stinging Nettle Leaves)

There are a lot of other herbs useful for supporting the respiratory system. The main focus would be to improve the production of surfactants in the lungs and reduce any pre-existing inflammation of irritation. The main class of herbs used for this effect are referred to as demulcents.

One thing to note is that demulcents should not be used during the infection as it can lead to further accumulation of fluid in the lungs if it turns into pneumonia. These herbs should only be considered for use prior to infection.

Useful Respiratory Herbs:

Goldenrod (Solidago canadensis)

Mullein (Verbascum thapsus)

Stinging nettle leaves (Urtica dioica)

Marshmallow root (Althaea officinalis)

Herbs For Protecting the Lungs From Inflammatory Damage:

Inflammation is another key area of focus to minimize the chances of experiencing lung damage as a result of the infection (brought on from inflammatory damage and direct damage to cells from the virus).

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) remains one of the biggest concerns for the infection.

A review article published in 2018 reviewed some of the most promising herbs and herbal extracts for resisting damage caused with ARDS [34]. Most of this research involves animal testing, so these effects are only in the very early stages. None of these studies can confirm these effects in humans, but provides reason to investigate further.

Here’s what the study found:

Ginseng (Panax ginseng) — The ginsenoside Rg5 has been shown to inhibit NF-kB in the lungs (animal studies) [24]

Alpinia Katsumadai Hayata — show to inhibit inflammation in mice via NF-kB pathway [25]

Licorice Root (Glycyrrhiza glabra) — A glycoside known as LicoA has been shown to inhibit inflammatory activity in the lungs (aninal study) [26]

Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) — Rosmarinic acid shown to protect lung injuries by blockinh inflammatory activity i mice [27]

Oregano (Origanum vulgare) — Also contains rosmarinic acid in significant amounts [27]

Spearmint (Mentha spicata) — also contains rosmarinic acid in significant amounts [27]

Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius) — May reduce lung damage resulting from inflammatory processes (animal models) [28].

Linalool — essential oil component in a wide-range of aromatic plant species. Shown to limit damage in an inflammatory lung-damage model [29]

Magnolia spp. — A compound known as Honokiol found in magnolia species may offer support against lung damage from septic shock (animal model) [30]

Turmeric Root (Curcuma longa) — The active constituent curcumin has been shown to be a potent inhibitor of the NF-kB pro-inflammatory compound [31].

Coleus forskohlii — Active compound Isoforskolin may protect the lungs from inflammatory lung damage (animal models) [32]

Ruscus aculeatus — Active ingredient ruscogenin may protect lungs from inflammatory damage (animal models) [33]

Final Thoughts: Herbal Medicine & COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic is taking the world by storm — causing people to take dramatic measures to isolate themselves and stop the spread of infection.

The best ways to avoid the infection — as per the advice of the WHO and CDC — is to wash your hands regularly throughout the day with soap and water, limit your exposure to public areas, avoid groups, and practice social distancing when forced to go out into public.

Other ways to reduce your chances of getting, and spreading the virus is to ensure you’re eating a healthy diet, getting in some exercise, avoiding smoking of any kind, and using herbal and nutritional supplements to strengthen potential weak spots that open us up to the virus.

No one measure is going to prevent the disease, but the accumulated effects of all the measures listed above will dramatically decrease your chances of getting sick.

To stay up to date with the outbreak as it develops, make sure to follow the official accounts of the CDC, WHO, and your local government’s department of health.

Author

Justin Cooke, BHSc

The Sunlight Experiment

(Updated March 15)

Popular Articles

References Cited

[1] Fleming, J. O. (1995). Coronaviruses. Journal of neurovirology, 1(5-6), 323-325.

[2] Cheng, P. W., Ng, L. T., Chiang, L. C., & Lin, C. C. (2006). Antiviral effects of saikosaponins on human coronavirus 229E in vitro. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology, 33(7), 612-616.

[3] Lin, C. W., Tsai, F. J., Tsai, C. H., Lai, C. C., Wan, L., Ho, T. Y., ... & Chao, P. D. L. (2005). Anti-SARS coronavirus 3C-like protease effects of Isatis indigotica root and plant-derived phenolic compounds. Antiviral research, 68(1), 36-42.

[4] Ryu, Y. B., Jeong, H. J., Kim, J. H., Kim, Y. M., Park, J. Y., Kim, D., ... & Rho, M. C. (2010). Biflavonoids from Torreya nucifera displaying SARS-CoV 3CLpro inhibition. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry, 18(22), 7940-7947.

[5] Li, S. Y., Chen, C., Zhang, H. Q., Guo, H. Y., Wang, H., Wang, L., ... & Li, R. S. (2005). Identification of natural compounds with antiviral activities against SARS-associated coronavirus. Antiviral research, 67(1), 18-23.

[6] Lau, K. M., Lee, K. M., Koon, C. M., Cheung, C. S. F., Lau, C. P., Ho, H. M., ... & Tsui, S. K. W. (2008). Immunomodulatory and anti-SARS activities of Houttuynia cordata. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 118(1), 79-85.

[7] Lin, L. T., Hsu, W. C., & Lin, C. C. (2014). Antiviral natural products and herbal medicines. Journal of traditional and complementary medicine, 4(1), 24-35.

[8] Weng, J. R., Lin, C. S., Lai, H. C., Lin, Y. P., Wang, C. Y., Tsai, Y. C., ... & Lin, C. W. (2019). Antiviral activity of Sambucus FormosanaNakai ethanol extract and related phenolic acid constituents against human coronavirus NL63. Virus Research, 273, 197767.

[9] Chen, C., Zuckerman, D. M., Brantley, S., Sharpe, M., Childress, K., Hoiczyk, E., & Pendleton, A. R. (2014). Sambucus nigra extracts inhibit infectious bronchitis virus at an early point during replication. BMC veterinary research, 10(1), 24.

[10] Lau, K. M., Lee, K. M., Koon, C. M., Cheung, C. S. F., Lau, C. P., Ho, H. M., ... & Tsui, S. K. W. (2008). Immunomodulatory and anti-SARS activities of Houttuynia cordata. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 118(1), 79-85.

[11] Bermejo, P., Abad, M. J., Díaz, A. M., Fernández, L., De Santos, J., Sanchez, S., ... & Irurzun, A. (2002). Antiviral activity of seven iridoids, three saikosaponins and one phenylpropanoid glycoside extracted from Bupleurum rigidum and Scrophularia scorodonia. Planta medica, 68(02), 106-110.

[12] Chiang, L. C., Ng, L. T., Liu, L. T., Shieh, D. E., & Lin, C. C. (2003). Cytotoxicity and anti-hepatitis B virus activities of saikosaponins from Bupleurum species. Planta medica, 69(08), 705-709.

[13] Ushio, Y., & Abe, H. (1992). Inactivation of measles virus and herpes simplex virus by saikosaponin d. Planta medica, 58(02), 171-173.

[14] Mehrotra, R., Ahmed, B., Vishwakarma, R. A., & Thakur, R. S. (1989). Verbacoside: a new luteolin glycoside from Verbascum thapsus. Journal of Natural Products, 52(3), 640-643.

[15] McCutcheon, A. R., Roberts, T. E., Gibbons, E., Ellis, S. M., Babiuk, L. A., Hancock, R. E. W., & Towers, G. H. N. (1995). Antiviral screening of British Columbian medicinal plants. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 49(2), 101-110.

[16] Turker, A. U., & Camper, N. D. (2002). Biological activity of common mullein, a medicinal plant. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 82(2-3), 117-125.

[17] Cowan, M. M. (1999). Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clinical microbiology reviews, 12(4), 564-582.

[18] Speranza, L., Franceschelli, S., Pesce, M., Menghini, L., Patruno, A., Vinciguerra, I., ... & Grilli, A. (2009). Anti-inflammatory properties of the plant Verbascum mallophorum. Journal of biological regulators and homeostatic agents, 23(3), 189-195.

[19] Jin, M., Zhao, K., Huang, Q., & Shang, P. (2014). Structural features and biological activities of the polysaccharides from Astragalus membranaceus. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 64, 257-266.

[20] Yuan, S. L., Piao, X. S., Li, D. F., Kim, S. W., Lee, H. S., & Guo, P. F. (2006). Effects of dietary Astragalus polysaccharide on growth performance and immune function in weaned pigs. Animal Science, 82(4), 501-507.

[21] Chen, H., Muhammad, I., Zhang, Y., Ren, Y., Zhang, R., Huang, X., ... & Abbas, G. (2019). Antiviral Activity Against Infectious Bronchitis Virus and Bioactive Components of Hypericum perforatum L. Frontiers in pharmacology, 10, 1272.

[22] Liu, W., & Li, H. (2020). COVID-19 Disease: ORF8 and Surface Glycoprotein Inhibit Heme Metabolism by Binding to Porphyrin.

[23] Wang C, Liu Z, Chen Z, Huang X, Xu M, He T, Zhang Z. (2020). The establishment of reference sequence for SARS-CoV-2 and variation analysis. Journal of Medical Virology

[24] Kim, T. W., Joh, E. H., Kim, B., & Kim, D. H. (2012). (2012). Ginsenoside Rg5 ameliorates lung inflammation in mice by inhibiting the binding of LPS to toll-like receptor-4 on macrophages. International immunopharmacology, 12(1), 110-116.

[25] Huo, M., Chen, N., Chi, G., Yuan, X., Guan, S., Li, H., ... & Ouyang, H. (2012). Traditional medicine alpinetin inhibits the inflammatory response in Raw 264.7 cells and mouse models. International immunopharmacology, 12(1), 241-248.

[26] Chu, X., Ci, X., Wei, M., Yang, X., Cao, Q., Guan, M., ... & Deng, X. (2012). Licochalcone a inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 60(15), 3947-3954.

[27] Chu, X., Ci, X., He, J., Jiang, L., Wei, M., Cao, Q., ... & Deng, X. (2012). Effects of a natural prolyl oligopeptidase inhibitor, rosmarinic acid, on lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. Molecules, 17(3), 3586-3598.

[28] Sun, C. Y., Pei, C. Q., Zang, B. X., Wang, L., & Jin, M. (2010). The ability of hydroxysafflor yellow a to attenuate lipopolysaccharide‐induced pulmonary inflammatory injury in mice. Phytotherapy Research, 24(12), 1788-1795.

[29] Huo, M., Cui, X., Xue, J., Chi, G., Gao, R., Deng, X., ... & Wang, D (2013). Anti-inflammatory effects of linalool in RAW 264.7 macrophages and lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury model. Journal of surgical research, 180(1), e47-e54

[30] Weng, T. I., Wu, H. Y., Kuo, C. W., & Liu, S. H. (2011). Honokiol rescues sepsis-associated acute lung injury and lethality via the inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammation. Intensive care medicine, 37(3), 533-541.

[31] Yuan, Z., Syed, M. A., Panchal, D., Rogers, D., Joo, M., & Sadikot, R. T. (2012). Curcumin mediated epigenetic modulation inhibits TREM-1 expression in response to lipopolysaccharide. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology, 44(11), 2032-2043.

[32] Yang, W., Qiang, D., Zhang, M., Ma, L., Zhang, Y., Qing, C., ... & Chen, Y. H. (2011). Isoforskolin pretreatment attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in animal models. International immunopharmacology, 11(6), 683-692.

[33] Sun, Q., Chen, L., Gao, M., Jiang, W., Shao, F., Li, J., ... & Yu, B. (2012). Ruscogenin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice: involvement of tissue factor, inducible NO synthase and nuclear factor (NF)-κB. International immunopharmacology, 12(1), 88-93.

[34] Patel, V. J., Biswas Roy, S., Mehta, H. J., Joo, M., & Sadikot, R. T. (2018). Alternative and natural therapies for acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. BioMed research international, 2018.

Monoamine oxidase has been linked with a variety of neurological disorders, and naturally, declines with age. Modern MAO inhibitors tend to come with a variety of undesirable side effects, pushing us to look for new MAO inhibitor options...