What is Slippery Elm?

Slippery elm is one of the best digestive demulcents around.

The inner bark of slippery elm is used as a nutritious gruel or topically as a poultice. The mucilage soothes and nourishes the mucous membranes, speeds wound healing and lowers pain — making it an excellent candidate for lower digestive tract disorders.

The mucilage content of slippery elm is also useful topically on the skin. This herb makes for a great poultice for inflamed, damaged, or irritated skin. The nutritious powder is placed in water to expand and become a thick paste, which is then applied to the surface of the skin and wrapped in a cloth or towel.

Slippery elm can be bought in bulk and made into topical poultices, mixed into a paste for a nutritious gruel, added to shakes, or bought pre-capsulated and taken that way. This is a great herb to keep around the house for its broad range of uses on inflammation and irritation.

Featured Slippery Elm

What is Slippery Elm Used For?

Slippery elm is mainly used for its demulcent and emollient activities to soothe the digestive, respiratory, and integumentary tissues.

Internally slippery elm is used for conditions including colitis, peptic, and duodenal ulcers, diarrhea, gastritis, IBD, and any condition involving inflammation in the digestive tract.

Topically, slippery elm is used to treat inflamed or irritated skin, burns, boils, and abscesses, or wounds.

+ Contraindications

May reduce the absorption of other herbs, nutrients, and medications.

Traditional Uses of Slippery Elm

The slippery elm inner bark is an official drug of the United States official pharmacopeia, where it is listed as a demulcent, emollient, and antitussive [3, 4]. It was a popular Native American remedy that was quickly adopted by European settlers. In the American civil war, it was commonly used as an effective wound healer among the soldiers [2].

Slippery elm inner bark powder was considered one of the best possible poultices for wounds and boils and all inflamed surfaces by the native American Indians [2, 4].

Slippery elm has been used traditionally to treat conditions affecting the digestive tract in much the same way that it is used today. Additionally, this herb has been used to treat vaginitis, mouth inflammation, hemorrhoids, anal fissures, varicose ulcers, abscesses, carbuncles, and various skin conditions [2, 5].

Herb Details: Slippery Elm

Weekly Dose

- (1:2 Liquid Extract)

30–140 mL - View Dosage Chart

Part Used

- Inner Bark

Family Name

- Ulmaceae

Distribution

- North America along the Eastern Coast

Herbal Actions:

- Demulcent

- Emollient

- Nutritive

- Expectorant

- Astringent

- Anti-inflammatory

- Antitussive

Constituents of Interest

- Mucilage

Common Names

- Slippery elm

- Red elm

- Gray elm

- Soft elm

- Moose elm

- Indian elm

- Sweet elm

- Winged elm

Duration of Use

- Caution advised with long-term use.

Botanical Information

Slippery elm is a member of the Ulmaceae family of plants, also known as the Elm family, which all have characteristically mucilaginous bark and leaves. This family contains only 7 genera and about 45 different species.

Habitat Ecology, & Distribution:

Ulmus rubra, otherwise known as red elm or slippery elm, is native to the eastern portions of North America, but can also be found growing in select areas of North America.

Slippery elm prefers dry, intermediate soils. [6].

Harvesting Collection, & Preparation:

It is generally recommended that 10-year-old bark is used [4].

The mucilage cannot be extracted by alcohol and only swells in water rather than dissolving into it [4].

The most common method of consuming slippery elm for nutritive purposes is to make a gruel, similar in texture to oatmeal. This can be made by mixing about 5 ml of slippery elm powder with cold water to make a paste. Boiling water is then added to the desired consistency, and can be flavored with sugar, honey, or spices such as cinnamon or nutmeg.

This is an excellent method of preparation to provide nutrition for infants and invalids [4].

Enemas can also be made from slippery elm bark (2 drachms) by mixing the powder with sugar (1 OZ) and olive oil (1 OZ) and warm milk (1/2 pint) and water (1/2 pint). This combination is suggested for constipation. [4].

Pharmacology & Medical Research

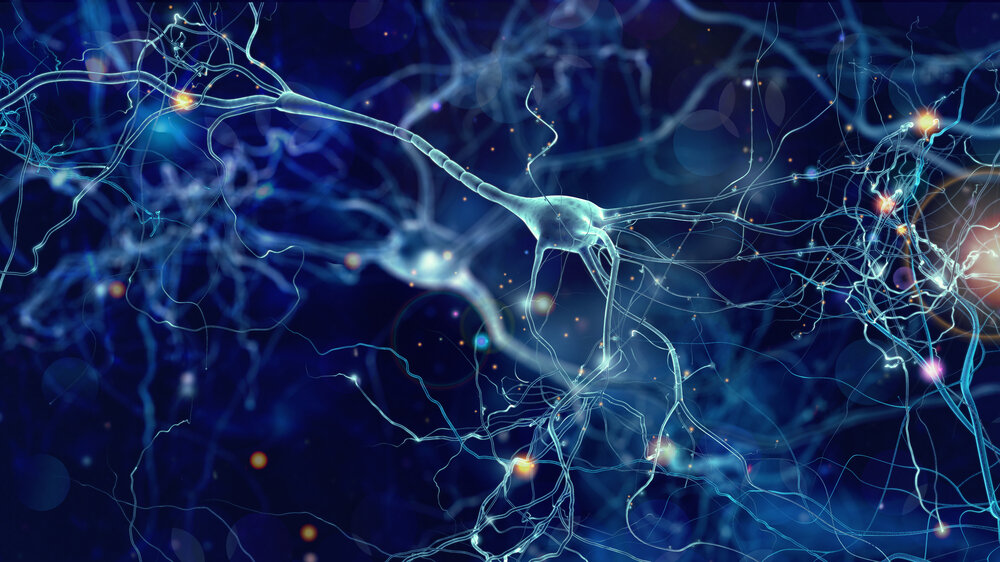

+ Demulcent/Emollient

Mucilages and mucilaginous plants are hydrophilic, which allows them to trap water. This causes them to swell in size, and develop a consistency similar to gel.

Gels, in general, tend towards having a soothing action on wounds such as burns, ulcers, and irritations. This action also affects the gastrointestinal tract when taken internally. They promote healing of mucosal layers and provide a protective barrier to the damaged tissue. [2, 10, 11].

Phytochemistry

| Chemical class | Chemical Name |

|---|---|

| Mucilage | Galactose, 3-methyl galactose, L-rhamnose, Galacturonic acid residues, glucose, polyuronides. |

| Tannins | Not listed |

| Sesquiterpenes | Not listed |

| Fatty acids | Capric acid, Caprylic acid, Decanoic acid, Oxalate acid. |

| Vitamins | Vitamin C, Thiamine |

| Minerals | Calcium, Iron, Zinc, Magnesium, Potassium. |

Clinical Applications Of Slippery Elm:

The high mucilage in slippery elm makes it useful for treating inflammatory conditions of the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and respiratory tract. It has mild antibacterial and antifungal actions and has significant vulnerary actions on the mucosal layer of the GIT.

The high vitamin and mineral content make it useful for conditions like anorexia and convalescence.

Topically, slippery elm is useful as a poultice for inflammed and damaged skin, and is useful for treating allergic reactions on the skin.

Cautions:

Slippery elm may reduce the absorbtion of other herbs or medications. Take away from all other supplements by at leas an hour before or after.

Synergy

Combine with licorice, marshmallow, and Pleurisy root for pleurisy [4].

Combine with male fern for tapeworms [4].

Essiac tea is a famous combination consisting of Ulmus rubra (slippery elm), Arctium lappa (burdock), Rumex acetosella (sorrel), and Rheum officinale (rhubarb).

This traditional herbal formula was developed by the Ojibwa tribe of Canada and used to treat conditions such as allergies, hypertension, and osteoporosis.

More recently essiac tea has been suggested for cancer. There have been a few studies conducted that indicate the usefulness of essiac tea for protecting the DNA of cells, and reducing the side effects of chemotherapy or radiation therapy in cancer patients. [2, 12].

Recent Blog Posts:

References:

Barnes, J., Anderson, L. A., & Phillipson, J. D. (2007). Herbal medicines (3rd ed.). London, United Kingdom: Pharmaceutical Press.(Pg. 545-546).

Braun, L., & Cohen, M. (2010). Herbs & natural supplements: An evidence-based guide Vol. 2. Sydney: Elsevier Australia. (Pg. 916-919).

Ulbricht C.E, Basch E.M, (2005). Natural standard herb and supplement reference. St. Louise: Mosby.

A Modern Herbal. (1931). Slippery Elm. Retrieved from http://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/e/elmsli09.html

Hoffmann, D. (2003). Medical herbalism: The science and practice of herbal medicine. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press. (Pg. 591)

US Forest Service. (n.d.). Ulmus rubra. Retrieved August 2, 2016, from http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/ulmrub/all.html

Beveridge R.J. (1969). Some structural features of the mucilage from the bark of Ulmus fulvus. Carbohydr Res 9 429-439

Duke, J. A. (2016). Dr Dukes phytochemical and ethnobotanical databases. Retrieved August 5, 2016, from https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/phytochem/plants/show/2060?qlookup=ulmus&offset=0&max=20&et=

Watts, C., & Rousseau, B. (2012). Slippery Elm, its Biochemistry, and use as a Complementary and Alternative Treatment for Laryngeal Irritation. Journal of Investigational Biochemistry, 17-23. doi:10.5455/jib.20120417052415

Mills, S., & Bone, K. (2000). Principles and practice of phytotherapy: Modern herbal medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Morton, J. (1990). Mucilaginous plants and their uses in medicine. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 29(3), 245-266. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(90)90036-s

Leonard, S. S., Keil, D., Mehlman, T., Proper, S., Shi, X., & Harris, G. K. (2006). Essiac tea: Scavenging of reactive oxygen species and effects on DNA damage. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 103(2), 288-296. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.09.013

Bean, W. J. (1970). Trees & Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles, 8th ed., p. 656. (2nd impression 1976) John Murray, London. ISBN 9780719517907

As COVID-19 continues to spread around the world, we’re getting a lot of questions on what the potential role of herbal medicine is during the outbreak. Learn how the virus works and how to limit your chances of transmission.