Passionflower has many uses and comes in many different varieties. The herb is mainly used for supporting anxiety and sleep but has a long list of other applications as well.

Black Horehound (Ballota nigra)

What is Black Horehound?

Black horehound is best known for its offensive odour — which resembles stale sweat.

Despite the unfortunate smell of this mint-relative, it has a lot to offer therapeutically.

Black horehound is one of the oldest medicinal herb species from Europe. It has a long history of use for infectious diseases including rabies and parasites, as well as for nausea and vomiting caused by neurological disorders.

This herb is a bit of a jack of all trades — but master of none. It offer reliable nervine, antispasmodic, antimicrobial, and anticholesterolaemic effects — all thanks to five unique phenylpropanoid glycosides contained in the leaves, stems, and roots of the herb.

What is Black Horehound Used For?

Many of the tradition uses of the herb have yet to be validated. The primary traditional uses for the herb that still stand today are for treating motion sickness or other causes of nausea or vomiting of neurological origin.

This herb is also still used as an antimicrobial for the digestive tract and topically on the skin.

Newer applications for the herb are aimed towards high cholesterol levels and diabetes.

Traditional Uses of Black Horehound

Black horehound was used for a lot of different applications. It was also a common remedy for motion sickness or any vomiting caused by neurological origins (rather than digestive).

Topically, the leaves were used to treat wounds, burns, and infection. Some herbalists even gave the herb as an enema for parasitic worms.

In Europe, where the herb originated from, the flowering tops were used to treat rabies after getting bitten by a rabid dog.

Herb Details: Black Horehound

Herbal Actions:

- Antibacterial

- Anticholesterolaemic

- Antiemetic

- Antifungal

- Antioxidant

- Antiprotozoal

- Antispasmodic

- Expectorant

- Hypoglycaemic

- Nervine

- Sedative

Weekly Dose

- (1:2 Liquid Extract)

10 20 mL - View Dosage Chart

Part Used

Flowering Tops

Family Name

Lamiaceae

Distribution

Europe & North America

Constituents of Interest

- Verbascoside

- Forsythoside B

- Arenarioside

- Ballotetroside

- Malic Acid

Common Names

- Black Horehound

- Black Stinking Horehound

- Fetid Horehound

- Stinking Roger

CYP450

- Unknown

Pregnancy

- Avoid black horehound if pregnant or breastfeeding

Duration of Use

- insert

Botanical Information

Black horehound originated from Europe but is now widespread across North America as well. The herb can grow over 1 meter tall and tends to grow on the side of the road in rural areas.

What this plant is best known for is its disagreeable odor — which can be described as stale sweat. The Greek name, ballo translates to “getting rid of”, or “throwing away”. This smell protects the herb by repelling both animals and humans.

Pharmacology & Medical Research

+ Anticholesterolaemic

One of the major causes of atherosclerosis is the result of oxidization of low-density lipoproteins LDL) [1].

Some of the phenolic compounds in black horehound (verbascoside, forsythoside B, arenarioside, and ballotetroside) were found to inhibit LDL oxidation through Cu2+ pathway [2].

+ Antimicrobial

Five phenolic compounds from black horehound were investigated to explore their antimicrobial potential. Of these five, three (verbascoside, forsythoside B, arenarioside) were found to have moderate activity against Proteus mirabilis, Salmonella typhi, and Staphylococcus aureus [3, 4].

Another study looked at the antimicrobial effects of each part of the plant (leaves, roots, and stems). The results suggested the crude extract of the roots had the best inhibitory activity on the strains tested (Enterococcus faecalis, Escherichia coli, Klensiella pneumonia, Proteus miribalis, Salmonella typhi, and Staphylococcus aureus, Aspergillus fumigates, Aspergillus niger, Fusarium solani, and Leishmania) [5]. The leaf and stem chloroform extracts had similar antimicrobial action.

+ Sedative

Phenylpropanoid compounds from black horehound were found to bind to benzodiazepine, dopaminergic, and morphinic receptors in animals [6, 4]. This provides a mechanism of action for the traditional sedative uses of the herb — but more research is needed to further elucidate these findings.

Phytochemistry

The flowering tops (the part used medicinally) are rich in diterpenoid lactones (labdane type) — such as ballotenol, ballotinone, 7alpha-acetoxymarrubiin, hispanolone, and preleosibirin.

The tops are also rich in phenolic compounds (luteolin-7-lactate, luteolin-7-glucosyl-lactate), phenylpropanoid glycosides (verbascoside, forsythoside B, arenarioside, ballotetroside), organic acids (quinic acid), and volatile oils.

Cautions & Safety Information:

Black horehound is considered a safe herb, with little chances of experiencing any side effects.

Allergies to the herb have been noted, so caution is advised if using the herb for the first time. Always start with a small amount first to see how you react before using a full dose.

Black horehound may interact with the following medication classes:

Antipsychotic medications (overlap in receptor activation)

Anti-Parkinson’s disease medications (overlap in dopaminergic action)

Sedatives (overlap in sedative effects and benzodiazepine receptor activation)

Iron supplements (black horehound has been suggested to prevent the absorption of iron)

Recent Blog Posts:

Featured Herb Monographs

References:

[1] — Steinberg, D. (1997). Low density lipoprotein oxidation and its pathobiological significance.

[2] — Seidel, V., Verholle, M., Malard, Y., Tillequin, F., Fruchart, J. C., Duriez, P., ... & Teissier, E. (2000). Phenylpropanoids from Ballota nigra L. inhibit in vitro LDL peroxidation.

[3] — Didry, N., Seidel, V., Dubreuil, L., Tillequin, F., & Bailleul, F. (1999). Isolation and antibacterial activity of phenylpropanoid derivatives from Ballota nigra.

[4] — Al-Snafi, A. E. (2015). The Pharmacological Importance of Ballota nigra–A review.

[5] — Ullah, N., Ahmad, I., & Ayaz, S. (2014). In vitro antimicrobial and antiprotozoal activities, phytochemical screening and heavy metals toxicity of different parts of Ballota nigra.

[6] — Daels-Rakotoarison, D. A., Seidel, V., Gressier, B., Brunet, C., Tillequin, F., Bailleul, F., ... & Cazin, J. C. (2000). Neurosedative and antioxidant activities of phenylpropanoids from Ballota nigra.

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa)

What is Kratom?

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) is a medicinal plant species native to Southeast Asia with powerful stimulating, pain-relieving, and euphoric effects.

As a member of the coffee family, it’s no surprise kratom is used to combat fatigue and work longer, more productive hours. But there are some other attributes to kratom that contradict this effect.

Kratom is stimulating in lower doses and sedative in higher doses. It acts on the opioid pain system and interacts with neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenaline.

This unique combination of relaxing, pain-killing, and stimulating effects gives kratom interesting applications. The most common use of the plant is to work longer hours, relieve joint and muscle pain, and help people with chronic pain transition away from highly addictive pain medications.

In this ultimate guide, we’ll cover everything you need to know about kratom.

Topics We'll Cover in This Monograph

1. What is kratom used for?

2. Kratom Technical Details

3. History of Kratom

4. Guide to Using Kratom Safely (Dosage Information

5. Kratom Strains (Red, White, Green)

6. Different Types of Kratom Products

7. Medical Research of Kratom

8. Kratom Active Constituents

9. Kratom Side Effects & Safety

10. Legality of Kratom Around the World

Let’s jump straight in. Feel free to jump around to the sections that interest you the most.

What is Kratom Used For?

There’s a few differences between how kratom is used today compared to its traditional uses.

Let’s cover each in more detail.

Traditional Uses of Kratom

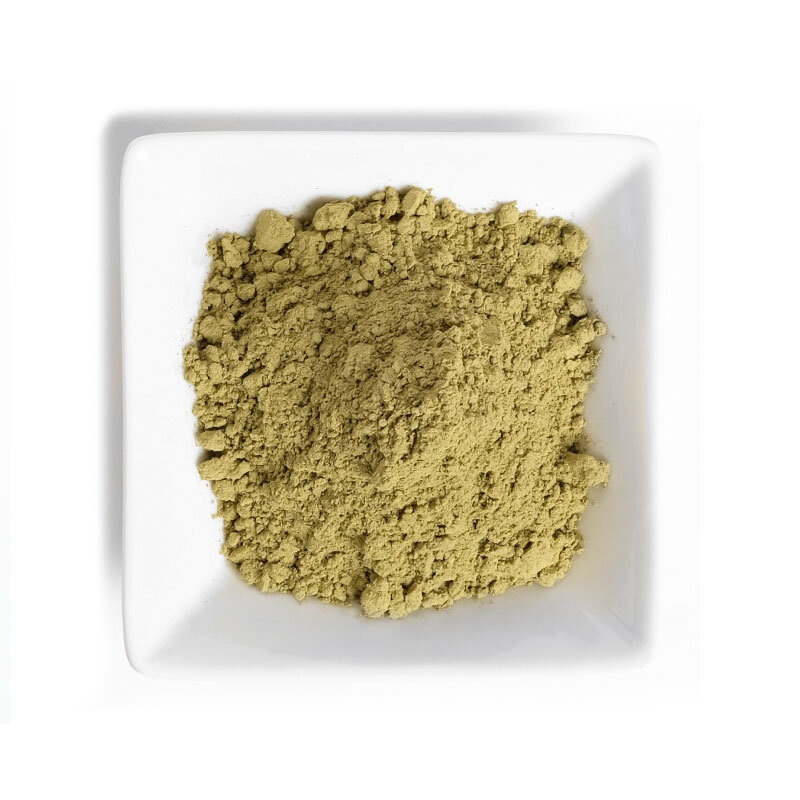

Traditionally, the leaves of the plant were chewed raw or made into a strong tea. This delivered much lower doses of the plant than modern methods allow.

In low doses, the effects of kratom are highly stimulating — very similar to coffee or yerba maté. Because of this, most traditional uses of this plant revolve around its stimulating effects.

Kratom was used by laborers as a way to combat fatigue during the long, hard working hours. Some reports even suggest kratom was used to increase the body’s tolerance to the effects of the hot sun. The pain-killing effects of the herb may have contributed to this by dulling body aches and pains while working.

Kratom was really a herb of productivity. If you took kratom while working, you could work harder, faster, and longer than normal — ultimately, getting more done in a day.

Other uses of the herb included treatment for intestinal infections, diarrhea, and muscle pain [5].

Modern Uses of Kratom

Modern applications of the herb are much more extensive because it’s easier now to choose between a low dose for stimulating effects or high doses for more sedative effects.

Kratom powders are readily available and don’t rely on chewing the leaves to release the active compounds. We also have access to high-potency tinctures, capsules, and resin extracts thanks to modern extraction technologies.

1. Kratom For Energy

We can split the uses of kratom according to the dose.

Lower doses of the plant (2.5 – 7 mg) are generally much more stimulating and have better mood-enhancing effects. This is the most common dosage taken traditionally by workers looking to leverage the energizing effects of the plant.

Many of the active ingredients in kratom stimulate the adrenergic receptors in the brain — causing increased electrical activity, faster heart rate, higher blood pressure, and more energy overall.

These effects can last anywhere from 4 to 8 hours on a single dose.

2. Kratom for Anxiety & Sleep

Larger doses (over 8 grams) are more sedative — making these doses better for supporting sleep and anxiety. However, this effect is less reliable than the other uses of kratom because of the stimulating activity at lower doses. Some people simply can’t take higher doses of the plant without experiencing side effects — which won’t help you with your sleep.

Some strains are better than others for sleep and anxiety, so make sure you find a strain recommended for these uses specifically.

3. Kratom & Opiate Withdrawal

One of the most important uses of the plant comes from its opioid effects. Kratom is able to curb opioid withdrawal symptoms, making it less likely for people to relapse during this uncomfortable stage of the recovery process.

4. Kratom for Pain Management

Kratom is a popular alternative for pain management for its opioid pain killing properties and lower likelihood of addiction. People use this plant to numb pain without having to take highly addictive opiate pain medications like morphine, vicodin, oxycontin, or others.

5. Kratom For Mood

The opioid effects of kratom impacts mood regulation. The cascade caused by opioid receptor activation releases dopamine in the reward center of the brain, producing a mild euphoria and sense of wellbeing.

Other alkaloids in the kratom plant target serotonin release — another neurotransmitter associated with mood.

Because of these effects, many people report benefits to using kratom as a way to stabilize low moods during waves of depression or during stressful times.

6. Kratom as an Immunomodulator

One of the more interesting applications of kratom currently under investigation is its ability to support the immune system. Many of the alkaloids and saponins found in kratom are also found in a plant called cat’s claw (Uncaria tomentosa) — which is well-known for its ability to boost the immune system and protect the body from cancer, viral infection, or autoimmune disease. These alkaloids stimulate parts of the immune system such as the Th1 immune response and various prostaglandins and leukotrienes.

Research is still needed to fully understand if kratom exerts these same effects.

Comparing the Applications of Kratom According to Dose

| Low Dose Applications of Kratom | High Dose Applications of Kratom |

|---|---|

|

|

Herb Details: Kratom

Herbal Actions:

- Sedative (High-Dose)

- Stimulant (Low-Dose)

- Analgesic

- Anxiolytic

- Nootropic (mild)

- Antimicrobial

- Antioxidant

Dose

- (Dried Powdered Herb)

2.5 to 15 grams

Part Used

Leaves

Family Name

Methysticum speciosa

Distribution

Southeast Asia

Constituents of Interest

- 7-Hydroxymitragynine

- Akuammiline

- Mitragynine

- Epicatechin

- Quinovic Acids

Common Names

- Kratom

- Kakuam

- Ketum

- Biak-biak

- Ithang

- Thom

CYP450

- Unknown

Pregnancy

- Avoid use during pregnancy.

Duration of Use

- Long-term use should be avoided to prevent addictive tendencies

A Brief History of Kratom

Kratom comes from various regions of Southeast Asia, including Thailand, Bali, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Papua New Guinea.

Here, kratom goes by the following names:

Kakuam

Ketum

Biak-biak

Ithang

Thom

In these regions, the leaves of the kratom tree are chewed or smoked throughout the day, or brewed into a strong tea and mixed with honey or citrus fruits. It was popular among laborers as a way to combat fatigue as they worked long hours throughout the day.

For centuries, kratom helped people work harder, hunt for longer hours in the day, and manage pain caused by injuries or infection.

It wasn’t until the 1800s that the Western world caught wind of kratom. A botanist travelling through Malaysia noted the herb as a substitute for opium — which, at the time, was already heavily restricted.

Interest in kratom began to spread throughout Europe and eventually, North America. Still, it wasn’t nearly as popular as a stimulant as coffee and couldn’t compete as a pain medication with pharmaceuticals. Only in the last ten years has kratom really become popular in the Western world as an alternative to pain medications as the epidemic of drug addiction is at an all-time high.

Kratom remains a popular alternative option in Europe and the United States for pain management alongside cannabidiol (CBD) — which are often taken together.

Beginner’s Guide to Using Kratom

Getting started with kratom is simple — once you have your kratom, the next step is to figure out how much you should take, and how to prepare it.

Kratom Dose: How Much Kratom Should I Take?

The general dosage range for kratom leaf powder is 2.5 to 15 grams.

Note that concentrates can vary significantly, so always follow the directions on the label when using these products.

Everybody responds to the effects of kratom a little differently — so, play it safe if this is your first time using kratom. Start with a very low dose (2 grams), and increase gradually over time as you start to get a feel for how kratom affects your body individually.

A good process for beginners is to start with about 2 grams, wait 30 minutes, and follow up with another 1 gram every 30 minutes until you reach the desired level of effects.

If you start to experience side effects, like kratom wobble (more on this later), it means you’ve reached your dosage limit for that strain of kratom.

Once you find a dosage that works well for your body with that particular strain, you can be more confident in taking that dose from the beginning the next time you take kratom.

If you have a food scale, weigh your kratom for accuracy.

If you don’t have a scale, you can also use measuring spoons to get approximate doses. Use the table below to find the approximate equivalent dose from grams to teaspoons and tablespoons.

Imperial to Metric Conversions

| Metric | Imperial |

|---|---|

| 2.5 Grams | 1 Teaspoon |

| 7 Grams | 1 Tablespoon |

How Do I Take Kratom?

There are two main methods of preparing kratom powder. Let’s go through the basic process for each method.

Method 1: Kratom Tea

This is the most common method of preparing kratom. All you need to do is mix your dose of kratom (2.5 – 15 grams) with about 500 mL or 1 L of boiling water.

Stir until the powder dissolves— you don’t want to end up with any clumps of undissolved kratom powder in the mix.

Once you’ve stirred the mixture for a minute or two, leave it for another couple of minutes to let the powder settle to the bottom of the cup.

Once there's a layer of sediment at the bottom, you can pour the kratom tea into drinking cups, making sure to avoid the sludge of undissolved kratom powder at the bottom.

The final step is to add honey or sugar to sweeten, and drink up!

Method 2: Toss & Wash

This is the simplest method. It’s not the most enjoyable, but it’s quick and requires little preparation.

All you have to do is measure out the dose of kratom you want to use (somewhere between 2.5 and 15 grams depending on personal preference).

The next step is to simply swallow the powder with a spoon and quickly rinse it down with some water, juice, milk, or other beverage.

The powder can be hard to swallow, so it’s better to try and take a few spoonfuls than to fit the entire dose in one spoon.

What Are the Different Kratom Strains?

Kratom contains an array of alkaloids, each with its own set of effects on the human body. Some are stimulating like caffeine from coffee, others activate the opioid pain receptors (relaxing and pain-killing effects), others work through completely different receptors in the central nervous system.

This means the effects of kratom depend highly on which alkaloids are most abundant in the leaves.

As with most plants, there are many forms of kratom — each producing their own ratio of active alkaloids — resulting in subtle changes in growth patterns such as, leaf and or vein color, and effect profiles.

We call these different forms of kratom strains.

Each strain of kratom adds its own twist on the general effect profile of the plant. All kratom has stimulating effects in low doses and sedative qualities in higher doses — however, some strains place more emphasis on one effect than the other. For example, some strains are better for pain (like Red Vein Borneo), while others have stronger immune supportive activity (like White Maeng Da).

Let’s cover the most common strains of kratom, what makes them unique, and what their effect profiles are.

There are a few different ways to catalog kratom strains, but I’ve found the best way is to look at the vein color of the plant. This gives us a clue as to which alkaloids are most prevalent in the sample, and therefore, what the effect profile is most likely to produce.

Let’s get into the details.

1. Red Vein Kratom

Red vein kratom is usually the best for fast-acting sedative action. These kratom strains tend to be rich in 7-Hydroxymitragynine compared to other colors (more on this alkaloid later).

Kratom with red leaf veins can be found all over Southeast Asia, as you’ll find from the list below — but most users report red vein kratom to have very similar effects regardless of its place of origin.

Most Popular Red Vein Kratom Strains

Maeng Da Thai — Red Vein

Red Vein Kali Powder

Red Vein Borneo

2. Green Vein Kratom

Kratom strains with green veins are widely considered to be the middle ground for kratom effects. This means they’re both stimulating and sedative, and offer good general effects towards pain, mood, and focus.

Covering both ends of the kratom spectrum, green vein can have many different effects, so the strain really does matter with these plants. Unlike white or red vein where the effects tend to be very similar no matter where the strain originates from.

Most Popular Green Vein Kratom Strains

Super Green Vein Malaysian

3. White Vein Kratom

White vein kratom has a low concentration of 7-Hydroxymitragynine.

Kratom with white veins tend to have more of a mind effect — increasing alertness and focus, as well as producing feelings of euphoria and improvements in mood.

Many users use white vein kratom in a similar manner to coffee or tea while working or studying. The effects of white vein kratom are more subtle than both red and green vein strains, and therefore, is a better option for daily use.

Most Popular White Vein Kratom Strains

Maeng Da Thai — White Vein

Sumatra White Vein

White Vein Borneo

What Forms of Kratom are Available?

There are a few different ways you can use kratom. The most popular method is to mix the dried, ground leaf powder with water to drink. This produces the strongest and most reliable level of effects but isn’t exactly an enjoyable beverage to drink.

Other ways people use kratom include capsules, kratom resin extracts, pre-mixed drinks, and alcohol or glycerine-based tinctures.

Let’s discuss the differences between each form of kratom and what the pros and cons of each are.

1. Kratom Powder

Kratom powder is the most versatile and cost-effective way of using kratom. You can mix it with water, juice or milk, or put it in capsules or tea bags yourself.

Traditionally, kratom leaves were chewed to get the effects of the plant. The chewing action breaks the leaves up, while enzymes in the saliva break down the cellular structure of the kratom cells — effectively releasing the active alkaloids into the body.

Modern techniques of drying and powdering the kratom replaces the job of chewing the leaves. All you need to do is find a way to get this leaf powder into the body for the effects to take hold.

Unfortunately, kratom has a strong bitter flavor, so it may be difficult to take the powder raw. For this reason, most people mix kratom with chocolate milk, fruit juice, or other drinks with a strong flavor to mask the bitterness of the kratom.

Pros

- Allows you to consume the entire leaf — which is the most efficient way of using kratom

- Powder is the most cost-effective way of using kratom

- Powders are the closest method to traditional kratom consumption

- Most kratom strains are available as a powder form

Cons

- Kratom powders don’t taste very good

- You need a fairly large dose of powder to feel the effects

- Kratom powders require a little bit of effort to prepare

2. Kratom Capsules

Another popular method of using kratom is to take them as a capsule. You can make capsules yourself by using a capsule-making machine and filling it with raw kratom leaf powder.

Commercially available kratom capsules are also available and are an excellent option for novice users.

Capsules allow you to take consistent doses of kratom and are one of the most convenient and discrete ways of using the herb. Nobody thinks twice when you take a capsule, as it looks a lot like a regular health supplement — while mixing the green, bitter powder into a drink may draw the attention of your coworkers.

Pros

- Discrete and convenient way of using kratom

- Provides consistent doses every time

Cons

- Not the cheapest way of using kratom

- You may need to take several capsules to feel the effects

- Not all strains are available in capsule form, unless you make them yourself from raw powder

3. Kratom Tinctures & Glycetracts

All herbs can be made into a tincture. The process involves rinsing the raw herb with alcohol, vegetable glycerine, or another solvent to extract the active ingredients through diffusion. Once most of the active compounds are removed from the leaves, the remaining fiber and cell structures of the plant are filtered out — leaving behind a liquid rich in active kratom compounds.

Tinctures allow you to take consistent doses of kratom without having to weigh the leaf powder. This method is more discrete and can be added to any beverage or taken directly in the mouth.

For even faster onset of effects, you can hold the tincture under the tongue where the kratom alkaloids will absorb through the microcapillaries located directly under the tongue — delivering the active compounds directly into the bloodstream.

You can make tinctures yourself from the leaf powder or buy commercially made products.

Pros

- One of the most convenient ways of using kratom

- Alcohol or vegetable glycerine preserve the kratom — dramatically increasing the shelf life

Cons

- Not the most cost-effective way of using kratom

- Some of the active compounds will be lost during the extraction process

- You may need to take fairly large amounts of the tincture to feel the effects

4. Kratom Resin Extracts

The active alkaloids of the kratom plant are most abundant in the plant's resin — which is a highly viscous fluid produced by the plant. This is where many active alkaloids are stored. Numerous plants have resins that can be removed and concentrated.

Kratom resin extracts are very popular and make using kratom super simple. Since this preparation has all the unnecessary plant parts removed (the fibers, cell walls, proteins, carbohydrates, etc.), you don’t need as much of this stuff to start feeling the effects.

For this reason, be very careful when using concentrated extracts. It doesn’t take much to go overboard with this stuff.

Pros

- Allows you to take much less kratom to experience the effects

Cons

- Kratom extracts are expensive

- The effect profile isn’t as robust as the raw plant material

How Does Kratom Work?

Kratom works primarily through the alkaloid content of the leaves. We’ll get into the details of what alkaloids are, and what the most important alkaloids in the kratom plant do in more detail later.

The most important thing to note here is that alkaloids tend to have powerful pharmacological effects on the human body because they have the ability to activate or inhibit various cell receptors around the body.

The human body uses receptors as a way to control cellular functions around the body. By activating or inhibiting these receptors, we can tell our cells to behave a certain way.

Caffeine for example, binds to the adenosine receptors which are responsible for making us sleepy. By binding to these receptors, it prevents this from happening — causing us to feel awake and alert.

In the kratom plant, there are over 24 different alkaloids — each with their own affinity for different receptors in the body.

The majority of effects from kratom rely on an activation of the opioid receptors (resulting in pain inhibition, sedation, and euphoria), and adrenergic receptors (causing the stimulating effects).

Some of these alkaloids have more novel effects such as, stimulating immune cells, modulating dopamine levels, or inhibiting noradrenaline.

Kratom is also rich in flavonoids, including epicatechin — which is one of the primary antioxidants found in green tea, chocolate, and grapes. These antioxidants provide protection from harmful free radicals and oxidative compounds we’re exposed to from the environment.

Pharmacology & Medical Research

Over the years, there’s been a lot of interest in kratom as a therapeutic agent. In the early 1980s, there was a particularly strong interest in the potential to use kratom as an alternative to addictive pain medications or for helping drug users wean themselves off the medication.

There’s also a wealth of research for using kratom for increasing energy levels, addressing anxiety symptoms, and alleviating opiate withdrawal symptoms.

Most of this research was done in the 1970s and 1980s before there was a sweeping ban of kratom in the United States and Europe. Although most of these bans have since been lifted, kratom research is not as abundant as it once was.

Another reason why research isn’t as common for kratom as other pant medicines is due to the incredible complexity of the plants constituents. There are at least 24 known alkaloids in kratom, each with their own potent effect profile. This makes it very hard to study the plant because there are so many variables. It’s much easier to study plants with one active ingredient than a plant with 24 or more active ingredients.

Nevertheless, I’ll break down some of the best research we have available for the most common applications of kratom.

+ Kratom For Energy

The earliest uses of kratom involve its stimulating properties. Several alkaloids in kratom activate the adrenergic receptors [5,6].

Hormones such as noradrenaline and adrenaline (catecholamines) activate the adrenergic receptors which causes several important changes in the body — namely, increased heart rate, blood pressure, and electrical activity in the brain. The result of these changes is what we commonly experience as the fight or flight response.

However, these effects are highly dose-dependent. Higher doses of kratom have much more sedative effects on the body as a result of the opioid activity of the plant [7].

+ Kratom for Opiate Addiction

The first suggestion that kratom could alleviate opiate withdrawal symptoms came from research published in the 1930s [3]. Since then, this application has gained a lot of attention.

So how does this work? What does the research suggest?

First, let’s discuss how opiate addiction works in the first place.

After frequent exposure to opioid drugs, the body begins to change its homeostatic balance as an attempt to resist the effects of the drug — resulting in what we call tolerance. Drug tolerance forces us to take larger doses of the drug to experience the same level of effects.

As soon as the drug-use stops, it’s metabolized and removed from the body. Unfortunately, the homeostatic changes the body made in response to the drug lead to a phenomenon known as withdrawal.

Withdrawal symptoms can last several days or weeks as the body struggles to readjust homeostatic mechanisms to reverse the adaptations made while taking the drug.

Opiate withdrawal can be severe — causing symptoms such as anxiety, insomnia, chills, fever, body aches, seizures, headaches, and hallucinations. These symptoms are often strong enough to force the user to seek out more of the drug to alleviate these symptoms — resulting in a relapse.

Therefore, one of the major goals of addiction treatment is to alleviate the symptoms of withdrawal while the user goes through the detox process.

The most common medications used for this stage are methadone and buprenorphine — however, both these medications can also lead to a second stage of opiate and opiate-like drug dependance.

Kratom is a strong candidate for opiate withdrawal symptoms because it has the potential to alleviate opiate withdrawal symptoms without possessing nearly the same chances of secondary addiction.

So how does this work? Is there any data to back this up?

Kratom alkaloids alleviate opioid withdrawal symptoms in zebrafish (a common model of addiction) [4].

Unfortunately, there aren’t many high-quality studies on this application of kratom. The best data we have at the moment involves anecdotal evidence of people who successfully weaned themselves off opiate drug addiction, and animal research including the study cited above.

It’s likely kratom’s effects on the opioid system are much more complicated than simply activating these receptors in place of the opioid medications. This could explain why kratom has a lower incidence of addiction compared to specific opioid agonist medications such as morphine, fentanyl, methadone, and oxycontin.

More research is needed to fully understand the role kratom might play in helping people wean off addictive opiate drugs like heroin, vicodin, morphine, fentanyl, and oxycontin.

+ Kratom For Pain

Since kratom is able to exert its effects through the opioid system, it’s not surprising the herb possesses pain-relieving benefits. The opioid system is integral to the transmission of pain from the body to the brain. Mu- and gamma-opioid receptors located in the spinal cord and brain regulate the transmission of pain signals.

By activating the opioid receptors, kratom inhibits pain signals and reduces both chronic and acute pain.

A study published in 2009, highlighted the pain-killing and anti-inflammatory effects of kratom [8]. The study gave rats a standardized extract of kratom known as MSM at doses of 100 and 200 mg/kg. A significant reduction in both inflammation and pain were noted in the rats following the treatment with kratom.

Researchers in the study suggested the anti-inflammatory effects were a result of lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase inhibition.

The pain-relief is likely a combined result of the anti-inflammatory effects and opioid receptor activation.

+ Kratom For Focus

Kratom alkaloids possess adrenergic [5] and serotonergic [9] activity. Additionally, through the opioid system, kratom alkaloids like mitragynine are theorized to possess secondary dopaminergic and GABAergic effects in the brain [10, 11].

All of these effects are associated with cognitive performance and focus. Many of the most popular cognitive enhancing supplements and medications rely on activating one or more of these pathways in the brain.

Although there’s no research currently available that explores this interaction more closely, there's plenty of anecdotal reports that suggest kratom can boost focus and attention — especially with white veined kratom strains.

This is another area where more research is welcomed to fully elucidate the applications of kratom.

Kratom Constituents: What Are Kratom Alkaloids?

Kratom is a rich source of indole and oxindole alkaloids similar to caffeine. It’s also rich in antioxidant flavonoids, and pharmacologically-active saponins and glycoside derivatives.

The main constituents of kratom are mitragynine, paynantheine, speciogynine, and 7-Hydroxymitragynine — which collectively make up around 90% of the alkaloid content of the plant.

The alkaloid content of kratom plants can vary significantly. Even within the same strain, the alkaloid content can change depending on how much rain there was during the growing season, the altitude in which the plants are grown, and how soon the leaves were harvested during the season.

It’s thought the kratom plant produces these alkaloids as a way to defend itself from insects and animals and as a way to store excess nitrogen.

A) Kratom Alkaloids

Alkaloids are notorious for having powerful pharmacological effects on the human body.

Some of the most well-known alkaloids include caffeine (stimulant), cocaine (stimulant), morphine (pain-killer), nicotine (stimulant), ephedrine (stimulant), and ibogaine (psychedelic).

Alkaloids can be beneficial to the body, but they can also be quite toxic — as with the case of strychnine, aconitine, or coniine.

Kratom is exceptionally rich in alkaloids — most of which have been confirmed to be pharmacologically active in humans.

By far the most abundant alkaloid in kratom is mitragynine, so most of the current research explores his compound. However, over 23 other alkaloids have also been discovered, many of which have been investigated more closely for their effects.

Some of these alkaloids are even found in other useful plant species such as yohimbe or cat’s claw — both of which have a great deal of research highlighting their effect profiles.

Let’s briefly explore each alkaloid in kratom and their interaction with the human body.

1. 7-Hydroxymitragynine

This alkaloid is analgesic, antitussive (inhibits coughing), and antidiarrheal [12]. It’s also considered one of the key mu-opioid receptor agonists and one of the main alkaloids in red vein kratom strains.

2. 9-Hydroxycorynantheidine

This alkaloid is a partial opioid agonist — which means it’s not as strong as other alkaloids in the plant at activating the opioid pain receptors. However, many experts believe this alkaloid works through a different mechanism and can amplify the pain-killing effects of other alkaloids like mitragynine or 7-hydroxymitragynine.

3. Ajmalicine

Ajmalicine is also found in another popular stimulating herb known as yohimbe and Rauwolfia serpentina. Extracts of this same alkaloid from the yohimbe plant is referred to as δ-yohimbine.

There’s actually a lot of information available on this alkaloid, and there are synthetic versions available used in the treatment of high blood pressure.

Ajmalicine is an α-1 adrenergic receptor antagonist, which goes against many of the other alkaloids in the plant. It’s believed this alkaloid works as a smooth muscle relaxant, mild sedative, and helps reduce some of the side effects of other prevalent kratom alkaloids.

4. Akuammiline

Akuammiline is in the indole class of alkaloids and is also found in abundance in the akuamma seed (Picralima nitida) — which is where the name comes from.

This compound is structurally very similar to yohimbine and mitragynine — and likely offers a similar set of effects.

5. Ciliaphylline

There isn’t much research available on ciliaphylline, but it’s believed to be analgesic and antitussive (cough-suppressant) from preliminary research.

6. Corynantheidine

This alkaloid is a mu-opioid antagonist — which works against many of the other alkaloids in the plant. This compound is also found in yohimbe and acts as an α1-adrenergic and α2-adrenergic receptor antagonist (inhibitor).

7. Corynanthine

There isn’t much research on this alkaloid currently available, but some studies observed it to provide mild calcium channel blocking activity.

8. Corynoxine A & B

These two alkaloids have dopaminergic, neuroprotective, and mild sedative effects. Corynoxine A is also found in the medicinal herb cat’s claw (Uncaria tomentosa).

9. Iso Mitraphylline

This compound is a potent immunostimulant — suggested to provide the marhodity of the immune supportive effects of kratom despite making up less than 1% of the total alkaloid profile of the plant.

10. Isopteropodine

Isopteropodine is another immunostimulant and a 5-HTP modulator and mood supportive. This compound is involved in the concentration and mood-enhancing effects of some kratom strains.

11. Isorhynchophylline

Isorhynchophylline is found in Chinese cat’s claw (Uncaria rhynchophylla) and has immunostimulating and calcium channel blocking effects [13]. There isn’t much research currently available on this particular alkaloid.

12. Mitragynine

Mitragynine is considered the primary alkaloid in the kratom plant, responsible for the majority of the plants effects. It was the first discovered, and makes up roughly 66% of the total alkaloid profile of the kratom plant.

This alkaloid is an opioid receptor agonist, miod adrenergic receptor agonist, and 5HT2A (serotonin) receptor agonist. Its primary effects are antitussive (cough suppressant), anti-diarrheal, analgesic (pain-relieving), and central nervous stimulant and sedative.

13. Mitraphylline

Mitraphylline is an oxindole alkaloid with vasodilating, blood pressure lowering, muscle relaxing, and diuretic activity.

14. Mitraversine

This alkaloid is sometimes found in kratom but is more commonly found in a closely related species — Mitragyna parvifolia.

15. Paynantheine

This alkaloid is the second most abundant alkaloid in most kratom strains (though not all). It’s a smooth muscle relaxant and has minor activity on the opioid and adrenergic receptors. There’s a synthetic version of this compound available at the moment undergoing preliminary research.

16. Rhynchophylline

Rhynchophylline is found in both kratom and Chinese cat’s claw (Uncaria rhynchophylla). It’s been studied for its hypotensive effects — which were noted to leave blood flow in the kidneys unaffected [13]. Decreased blood flow in the kidneys is a serious side effect of modern pharmaceutical blood pressure medications — so there’s a lot of interest in this compound as a potential new blood pressure medication.

This alkaloid is also suggested to be an anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, NMDA receptor agonist, dopaminergic, serotonergic, and antiarrhythmic through calcium channel blocking activity. All of these suggested effects need to be studied in further detail to confirm.

17. Speciociliatine

This compound is a diastereomer of mitragynine — which means it’s very similar in structure to mitragynine.

This alkaloid is a weak opioid agonist and may inhibit acetylcholine release from presynaptic nerve terminals.

18. Speciogynine

This alkaloid is very similar in structure to the primary kratom alkaloid mitragynine and the third most abundant alkaloid in the plant. It’s thought to have muscle relaxant properties, and is attributed for a lot of kratoms stress-reduction effects.

19. Speciophylline

Speciophylline is another alkaloid kratom that has in common with cat’s claw. There isn’t much research on this compound, but early research suggests it may have anticancer activity — specifically towards leukemia cell lines.

B) Other Compounds in Kratom

1. Epicatechin

Epicatechin is a flavonoid with potent antioxidant effect. It’s abundant in the plant kingdom, best known for its role in providing many of the health benefits of green tea (Camellia sinensis), chocolate (Theobroma cacao), and grapes (Vitis vinifera).

2. Daucosterol

Daucosterol is classified as a saponin — which is another class of compound that often possess pharmacologically active effects in animals. This particular saponin is thought to contribute to the anti-inflammatory activity of kratom. It’s been shown to induce Th1 immune responses in animals [15] — which is a key component of a healthy immune system.

Daucosterol has also been shown to promote the regeneration of neural stem cells in vitro [16].

3. Quinovic Acids

Kratom shares a lot in common with cat’s claw — one of the world's premier immune-supportive herbs. Quinovic acids are another group of compounds the two herbs have in common.

Quibovic acids are classified as triterpene saponins. They’ve been shown to have potent antiviral activity in vitro [17], though more research is needed to see if this effect applies in living animals as well.

Safety & Side-Effects of Kratom

Caution is advised whenever using kratom. The effects can be very unpredictable, and the oposing effects some strains have from each other make it unreliable as a form of treatment for many conditions. If using kratom for its stimulating effects but sedation is delivered the condition can worsen. Only use kratom with the advice or observation of an experienced individual and only for minor conditions. Speak with your doctor before trying kratom is taking any medications or if you have any medical conditions.

Kratom Side Effects

Kratom doesn’t come without side effects — however, with responsible use the side effects of kratom acan be managed and mitigated.

The primary activity of kratom works through the opioid receptors and adrenergic receptors — so naturally, the most common side effects of the plant stem from the interaction with these receptors.

Adrenergic side effects cause a similar set of side effects of stress. This is because the adrenergic system is closely associated with the stress response.

Adrenergic side effects of kratom:

Nausea

Dizziness

Anxiety

Stimulation

Insomnia

Dry mouth

Headaches

Irritability

Sweating

Diarrhea

Increased urination

Rapid heartbeat

The opioid effects of kratom may produce a completely different set of side effects which are similar to other opioid medications.

Opioid side effects of kratom:

Sedation

Lethargy

Nausea or vomiting

Dizziness

Itchy nose

Euphoria

Constipation

Increased urination

Despite the fact that most of these side effects are very rare and only tend to show up if kratom is used in high doses, it’s important to consider the potential dangers of using kratom. As with any compound, you can always take too much. Be responsible when taking kratom and listen to your body.

With that said, there’s a trio set of side effects that many users experience if they take too much. These side effects are one of the main reasons kratom doesn't tend to cause addiction. To take enough kratom to “nod out” — which is the goal for a lot of recreational users, you're more than likely to experience something called the kratom wobble before you get enough of the herb to start nodding out.

What Is the “Kratom Wobble?”

So-called kratom wobble is the most common side effect from high doses of kratom. It causes dizziness and loss of coordination. It can make users feel quite unwell.

Kratom wobble has 3 main symptoms:

Blurry vision

Dizziness

Nausea/Vomiting

These effects are more common in some strains of kratom than others. The likelihood a specific kratom is to cause these side effects is called the wobble threshold.

Strains with a low wobble threshold are more likely to cause wobble side effects if you take too much. Strains with a high wobble threshold will have a much lower chance of causing these effects if you go slightly over the optimal dose for your body.

The lower the wobble threshold, the more likely that strain is of causing kratom wobble — especially in higher doses.

What Happens if I Experience Kratom Wobble?

The first thing you need to do when you experience wobble effects is to relax. Panicking is only going to amplify the effects. Instead, find somewhere comfortable to sit or lay down and gather yourself. The effects will usually pass within a few minutes but may last up to 3 hours.

Many people find it helps to drink ginger tea or warm water.

If you experienced wobble while taking kratom, make sure to reduce the dose the next time you take kratom, or find a strain that’s less likely to cause these effects.

The most common cause for kratom wobble is taking too much. This is a sign you’ve hit your dose limit for that particular strain of kratom.

Is Kratom Dangerous?

Just about everything is dangerous if you take enough of it — kratom is no different. There have been some reports of people dying from kratom — however, this is over-sensationalized in media reports. In most of these cases, kratom was abused or mixed with other drugs.

Never do this.

Kratom is a powerful medicinal plant and should be treated with respect.

Stick within the recommended dosage limits, don’t mix kratom with other drugs or medications, and listen to what your body is telling you.

There are plenty of safety studies on kratom — the majority of which report little to no toxicity even in very high doses. An older study (1972) investigating the safety profile of the main alkaloid in kratom — mitragynine — found that even after significantly high doses (920 mg/kg), there were no deaths [2].

This is an insanely high dose. In the average 150 lbs. person, this is the equivalent of over 62,000 mg of kratom (62 grams).

That’s five times the high-end of the recommended dose and nine times the average 7 g dose.

Is Kratom Addictive?

The most concerning potential long-term side effect of kratom use is addiction.

Kratom is an opioid agonist, much the same way oxycontin or heroin is — however, unlike these pharmaceuticals, kratom contains dozens of active ingredients, each acting on different pathways in the body. This gives kratom a more rounded effect profile and has a much lower chance of leading to addiction.

In fact, kratom is often limited in its addictive qualities because the dose can only go so high before it causes the user to feel kratom wobble or other unwanted side effects. You can’t get high from kratom the same way you can with pharmaceutical opioid drugs.

Short term, low dose, or sporadic use of the plant is highly unlikely to result in addiction and is even used to help wean people off addictive drugs.

With that said, be careful when using opioid agonist plants or medications. Speak with your doctor before using the plant if you have a history of addiction — especially to opiate-based drugs or medications.

Kratom Legality

Kratom has a shaky legal history. It’s been banned, unbanned, and banned again all around the world. The laws on whether or not you can order kratom can be difficult to navigate.

Here’s a brief overview on the current legal climate around kratom.

Is Kratom Legal in the United States?

In the United States, kratom was banned, then unbanned, then banned again. It’s a rollercoaster ride trying to keep up with the changing laws. The argument goes back and forth whether kratom is useful for avoiding or treating addiction or if it causes addiction.

At the moment, kratom is legal on a federal level and banned in specific states or municipalities.

+ States Where Kratom is Banned

- Alabama

- Arkansas

- Indiana

- Rhode Island

- Vermont

- Wisconsin

In some states, the laws aren't black and white. For example, kratom is legal in the state of California, but banned in the city of San Diego. There are similar examples of this in Florida, where kratom is only banned in the Sarasota county.

+ States Where Kratom is Legal

- Alaska

- Arizona

- California (Except San Diego)

- Colorado (Except Denver)

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- Florida (Except Sarasota county)

- Georgia

- Hawaii

- Idaho

- Illinois (Except Jerseyville)

- Iowa

- Kansas

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maine

- Maryland

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi (Except Union County)

- Missouri

- Montana

- Nebraska

- Nevada

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Mexico

- New York

- North Carolina

- North Dakota

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Pennsylvania

- South Carolina

- South Dakota

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Utah

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Wyoming

Is Kratom Legal In Europe?

Kratom is very hit/miss in Europe. Some countries have decided to ban the plant because of fears of addiction, while others allow its use as a way for people to avoid addiction to prescription medications.

+ Legal

- Austria

- Belarus

- Belgium

- Bulgaria

- Croatia

- Czech Republic

- France

- Germany

- Greece

- Holland

- Hungary

- Moldova

- Netherlands

- Norway

- Portugal

+ Illegal

- Ireland

- Italy

- Latvia

- Lithuania

- Poland

- Romania

- Russia

- Sweden

- Turkey

- United Kingdom

- Denmark

- Finland

Is Kratom Legal in Asia and Australasia?

Starting with Thailand in 1943, and neighboring countries in the years following, kratom use and cultivation were banned. There’s a lot of conspiracy around this which we’ll get into later in the “Is Kratom Legal Where I Live” section.

To summarize, many people believe it was the pharmaceutical companies that lobbied against kratom because it was widely used by people as a substitute for opioid medications or to wean opiate addicts off these drugs. The main argument is that kratom is significantly less addictive than these medications, and despite the potential for uncomfortable side effects, the herb is much safer than prescription pain medications.

Nevertheless, kratom was banned in Thailand, and massive fines were given to anybody caught using, or growing the herb. Later in 2018, these laws were finally redacted and kratom is now a major economic export for the country.

Other Southeast Asian countries have had similar bans on kratom — many of which have been overturned.

+ Legal

- Thailand (medicinal only)

- Bali

- China (legal grey-area)

+ Illegal

- Malaysia

- South Korea

- Australia

- Japan

- New Zealand

- Myanmar

- Singapore

- Vietnam

Final Thoughts: Kratoms Usefulness & Safety index

Kratom is an incredibly useful plant. It has stimulating effects similar to coffee or tea in lower doses and sedative effects similar to kava in higher doses. It has powerful pain-killing activity and can even be used to boost mood and our immune systems.

The contradictory set of effects kratom provides have boggled researchers for decades as they try to decipher the interaction between dozens of active alkaloids and other phytochemicals found in the plant.

After a few decades of banishment in the United States and much of Europe, the research on these chemicals fell out of interest. Only within the last 10 years or so has interest in the plant peaked again and research resumed.

Many people are finding usefulness for the plant as an alternative to coffee in the morning, for managing chronic or tough to treat pain without having to take pharmaceutical pain medications, boost focus and concentration, or stabilize mood.

As with any powerful medicine, it’s important you treat kratom with respect if you want to avoid side effects and stay safe.

Author:

Justin Cooke, BHSc

The Sunlight Experiment

Recent Blog Posts:

Popular Herbal Monographs

References

[1] — Jansen, K. L., & Prast, C. J. (1988). Ethnopharmacology of kratom and the Mitragyna alkaloids. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 23(1), 115-119.

[2] — Macko, E., Weisbach, J. A., & Douglas, B. (1972). Some observations on the pharmacology of mitragynine. Archives internationales de pharmacodynamie et de thérapie, 198(1), 145.

[3] — Jansen, K. L., & Prast, C. J. (1988). Psychoactive properties of mitragynine (kratom). Journal of psychoactive drugs, 20(4), 455-457.

[4] — Khor, B. S., Jamil, M. F. A., Adenan, M. I., & Shu-Chien, A. C. (2011). Mitragynine attenuates withdrawal syndrome in morphine-withdrawn zebrafish. PLoS One, 6(12).

[5] — Hassan, Z., Muzaimi, M., Navaratnam, V., Yusoff, N. H., Suhaimi, F. W., Vadivelu, R., ... & Jayabalan, N. (2013). From Kratom to mitragynine and its derivatives: physiological and behavioural effects related to use, abuse, and addiction. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(2), 138-151.

[6] — Beckett, A. H., Shellard, E. J., & Tackie, A. N. (1965). The Mitragyna Species of Species of Asia-Part IV. The alkaloids of the leaves of Mitragyna speciosa Korth.. Isolation of Mitragynine and Speciofoline1. Isolation of Mitragynine and Speciofoline1. Planta Medica, 13(02), 241-246.

[7] — Prozialeck, W. C., Jivan, J. K., & Andurkar, S. V. (2012). Pharmacology of kratom: an emerging botanical agent with stimulant, analgesic and opioid-like effects. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, 112(12), 792-799.

[8] — Mossadeq, W. S., Sulaiman, M. R., Mohamad, T. T., Chiong, H. S., Zakaria, Z. A., Jabit, M. L., ... & Israf, D. A. (2009). Anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects of Mitragyna speciosa Korth methanolic extract. Medical Principles and Practice, 18(5), 378-384.

[9] — Matsumoto, K., Mizowaki, M., Suchitra, T., Murakami, Y., Takayama, H., Sakai, S. I., ... & Watanabe, H. (1996). Central antinociceptive effects of mitragynine in mice: contribution of descending noradrenergic and serotonergic systems. European Journal of Pharmacology, 317(1), 75-81.

[10] — Klitenick, M. A., DeWitte, P., & Kalivas, P. W. (1992). Regulation of somatodendritic dopamine release in the ventral tegmental area by opioids and GABA: an in vivo microdialysis study. Journal of Neuroscience, 12(7), 2623-2632.

[11] — Sasaki, K., Fan, L. W., Tien, L. T., Ma, T., Loh, H. H., & Ho, K. (2002). The interaction of morphine and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) ergic systems in anxiolytic behavior: using μ-opioid receptor knockout mice. Brain research bulletin, 57(5), 689-694.

[12] — Ponglux, D., Wongseripipatana, S., Takayama, H., Kikuchi, M., Kurihara, M., Kitajima, M., ... & Sakai, S. I. (1994). A new indole alkaloid, 7 α-hydroxy-7H-mitragynine, from Mitragyna speciosa in Thailand. Planta medica, 60(06), 580-581.

[13] — Shi, J. S., Yu, J. X., Chen, X. P., & Xu, R. X. (2003). Pharmacological actions of Uncaria alkaloids, rhynchophylline and isorhynchophylline. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, 24(2), 97-101.

[14] — León, F., Habib, E., Adkins, J. E., Furr, E. B., McCurdy, C. R., & Cutler, S. J. (2009). Phytochemical characterization of the leaves of Mitragyna speciosa grown in the USA. Natural product communications, 4(7), 1934578X0900400705.

[15] — Lee, J. H., Lee, J. Y., Park, J. H., Jung, H. S., Kim, J. S., Kang, S. S., ... & Han, Y. (2007). Immunoregulatory activity by daucosterol, a β-sitosterol glucoside, induces protective Th1 immune response against disseminated Candidiasis in mice. Vaccine, 25(19), 3834-3840.

[16] — Jiang, L. H., Yang, N. Y., Yuan, X. L., Zou, Y. J., Zhao, F. M., Chen, J. P., ... & Lu, D. X. (2014). Daucosterol promotes the proliferation of neural stem cells. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology, 140, 90-99.

[17] — Aquino, R., De Simone, F., Pizza, C., Conti, C., & Stein, M. L. (1989). Plant Metabolites. Structure and In Vitro Antiviral Activity of Quinovic Acid Glycosides from Uncaria tomentosa and Guettarda platypoda. Journal of natural products, 52(4), 679-685.

Kava (Piper methysticum)

Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera)

Cannabis (Cannabis sativa/indica)

Cannabis Overview

Cannabis is well known for its psychoactive effects, causing temporary changes in visual and auditory perception.

The cannabis plant is also a rich source of medicinal compounds. Cannabinoids related to THC exert medicinal action through the endocannabinoid system — a critical component of homeostasis.

Many of these cannabinoids aren't psychoactive, and wont produce the 'high' associated with the plant in their isolated forms.

Compounds like CBD, have become especially popular as a supplement recently for its broad medicinal benefits.

There are plenty of uses for cannabis — however, product selection, strain choice, and cannabinoid profiles make a big difference in the effects produced by the plant. It's important to use the right type of cannabis for the job.

What is Cannabis Used For?

Using cannabis as medicine poses challenges due to the large variety of effects each cannabinoid possesses. Different cannabinoid and terpene ratios can produce different effect profiles.

The plant has many claimed benefits, and though a lot of them can be validated, it's not a miracle plant.

Cannabis is especially reliable for a few key symptoms:

- Lowering various forms of inflammation

- Improving microbiome diversity (through CB2 receptor activity)

- Reducing nervous excitability

- Reducing convulsions

- Improving sleep onset and maintenance

- Lowering pain

Using cannabis as medicine should be attempted with caution due to the degree of variability the plant produces in terms of effect profile. What this means is that some cannabis extracts will make symptoms like anxiety worse, while others can dramatically improve it.

Choosing the right strain or extract is of the utmost importance when using cannabis as medicine.

The effects of cannabis can be contradictory:

- It's both a stimulant and a sedative

- It increases appetite, and suppresses it

- It increases immune activity, and suppresses inflamamtion

These effects all contradict themselves in most cases. The reason this happens is because the cannabinoids work through a regulatory pathway (endocannabinoid system) rather than on a particular organ function.

It's similar to how adaptogens like ginseng, ashwagandha, or reishi produce often contradictory or bidirectional results.

+ Indications

- Anorexia

- Cancer

- Crohn's disease

- Dystonia

- Epilepsy

- General anxiety disorder

- Glaucoma

- Gout

- Insomnia

- Menstrual cramping

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Neuropathic pain

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Schizophrenia (Caution)

- Social anxiety disorder

- Substance abuse/addiction

- Ulcerative colitis

+ Contraindications

- Only use cannabis medicinally following the direction of a qualified medical practitioner.

- Caution with anxious or depression.

- May worsen symptoms of psychosis

- Avoid use alongside medications unless first discussing with your doctor.

+ Potential Side-Effects

- Apathy (long-term use)

- Bronchitis (smoking)

- Cough (smoking)

- Depression

- Dizziness

- Dry eyes

- Dry mouth

- Eye reddening

- Fatigue

- Hallucinations

- Headache

- Heart palpitations

- Hypertension/Hypotension

- Increased appetite

- Lightheadedness

- Menstrual changes

- Nausea/vomiting

- Numbness

- Paranoia

- Tachycardia

Herb Details: Cannabis

Weekly Dose

- (CBD content in mg)

70–700 mg - View Dosage Chart

Part Used

- Leaves, flowers, seeds

Family Name

- Cannabacea

Distribution

- Worldwide

Herbal Actions:

- Sedative/Stimulant

- Anti-emetic

- Anti-spasmodic

- Anti-convulsant

- Analgesic

- Antinflammatory

- Appetite Suppressant/Stimulant

- Adaptogen

- Anti-cancer

- Antioxidant

Common Names

- Cannabis

- Marijuana

- Hemp

- Mary Jane

- Herb

Pregnancy

- Avoid use while pregnant and nursing.

Duration of Use

- Long-term use acceptable. Recommended to take breaks periodically.

CYP450

- CYP2C9

- CYP3A4

Botanical Information

Cannabis plants are members of the Cannabacea family. This small family comprises only 11 different genuses, and about 170 species.

Some common members of the family are hops (Humulus spp.) and celtis (Celtis spp.). The celtis genus contains the largest collection of species by far, with over 100 different species. Cannabis and Humulus are the closest related genus' in the group by far.

There are three species of cannabis:

1. Cannabis sativa

Cannabis sativa is a tall, fibrous plant. It's high in cannabinoids, terpenes, and other phytochemicals — giving it many uses medicinally.

Cannabis sativa is the most commonly cultivated species. There are hundreds, if not thousands of different phenotypes of this species — the most important being hemp — which is a non-psychoactive, high fiber plant valued as both a health supplement and textile. It's also used for food (seeds), and to make biodeisel.

There are also Cannabis sativa strains high in the psychoactive component — THC — which make it popular as both medicine and recreational intoxicant.

2. Cannabis indica

Cannabis indica grows as s shorter, bushier plant. It's hgiher in THC, and there are few low-THC phenotypes available for this plant.

This species of cannabis is most often used recreationally.

3. Cannabis ruderalis

Cannabis ruderalis is a small, herbaceus plant more closely related to Cannabis sativa than Cannabis indica. It's low in cannabinoids, and terpenes, as well as fiber — limiting its value to humans.

This species has the unique ability to initiate flower production irrelevant to day length. Plant breeders have started mixing the plant with other species to gain these benefits. This makes cultivation easier in areas where day length is too short or too long for optimal cannabis cultivation.

Phytochemistry

There are 421 compounds in the cannabis plant [1], at least 66 of these are cannabinoids — some sources report as many as 112.

The top 6 cannabinoids in the plant (CBD, CBG, CNN, THC, THCV, and CBC), account for the vast majority of the cannabinoid profile.

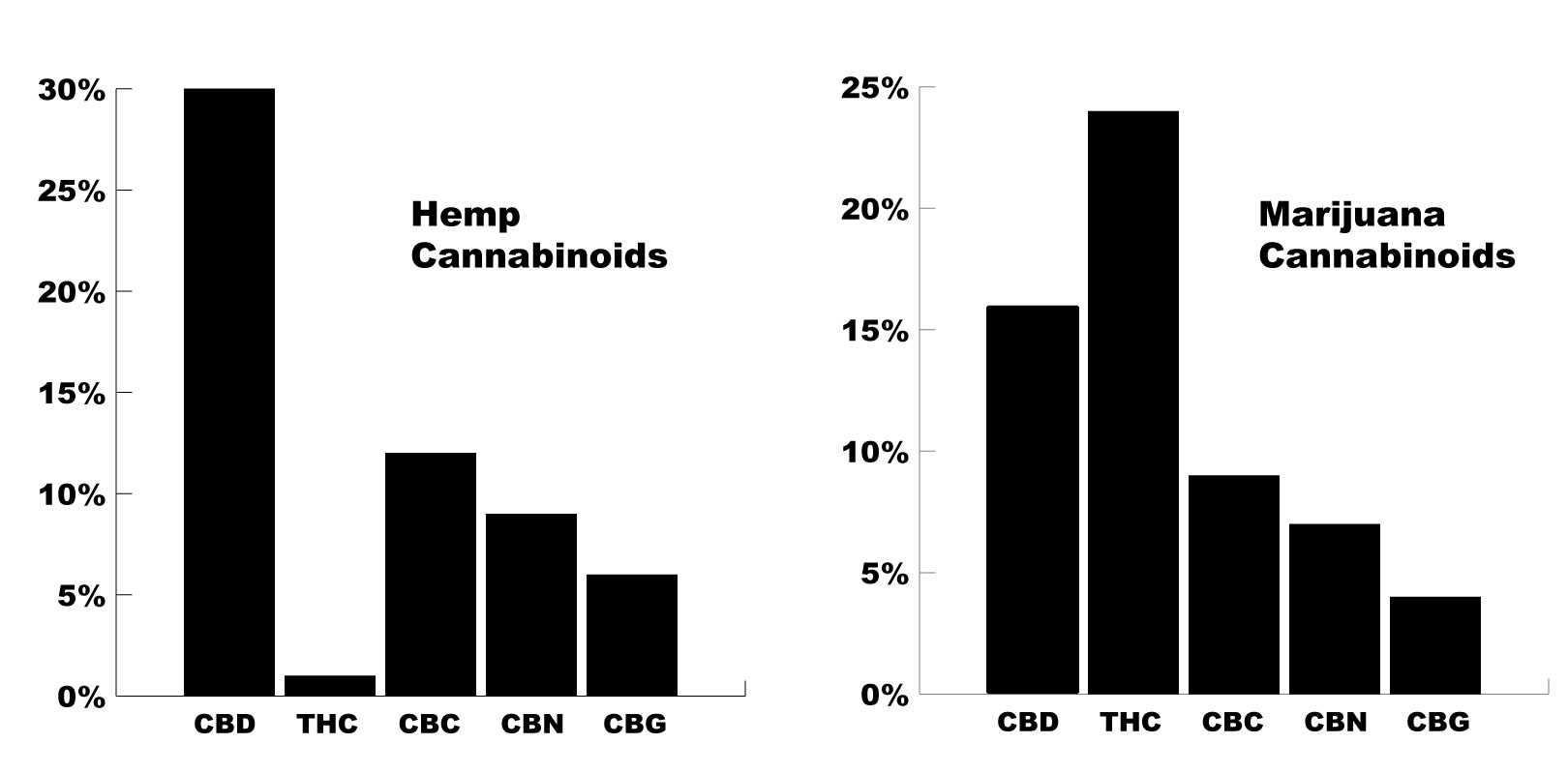

The phenotype of the cannabis used is the primary determining factor for the cannabinoid profile of each plant.

Hemp plants for example, contain much higher levels of CBD, and lower levels of THC. Marijuana strains are the opposite, contianing high THC, and lower CBD.

Depending on the strain, this can vary dramatically — and you can find almost any combination of cannabinoid possible.

The Cannabinoids:

Cannabinoids are a class of phytochemical compounds resembling the structure of our naturally occurring ecosanoid endocannabinoids; anandamide, and 2-AG. There are roughly 66 of these compounds in the cannabis plant, and a few found in other species of plants as well — such as helichrysum and echinacea.

Although the cannabinoids are very similar, their binding activity varies a lot [14]. Some bind to CB1 receptors (located primarily in the central nervous system), others bind to CB2 receptors (found primarily in immune tissue). Some cannabinoids will even bind to both, or work by increasing the concentrations of naturally occurring endocannabinoids instead.

Due to the wide range of variability between each cannabinoid, it’s useful to go over them in greater detail individually.

1. CBC

Cannabichromene

CBC is the third most abundant cannabinoid in the cannabis plant.

It’s non-psychoactive.

CBC is far less studied than the two preceding cannabinoids CBD, and THC, though early research is starting to suggest it’s even better for treating conditions like anxiety than the famed CBD.

CBC content can be increased in the cannabis plant by inducing light-stress on the plant [5].

CBC Medicinal Actions

Antidepressant

Mild sedative

Receptors Affected

Vanilloid receptor agonist (TRPV3 and TRPV4) [4]

2. CBD

Cannabidiol

In many cases, CBD is the most abundant cannabinoid. Only selectively bred cannabis strains will have higher THC concentrations than CBD.

CBD is famed for many reasons. It offers a wide range of medicinal benefits, and has been well-studied and validated over the past two decades.

CBD oils, e-liquids, and edibles have become highly popular in recent years as more of this research is being released and translated for the general public.

CBD Medicinal Actions

Antinflammatory

Mild appetite suppressant

Lowers stress

Adaptogenic

Mild sedative

Anti-emetic

Receptors Affected

Adenosine (A2a) reuptake inhibitor [6]

Vanilloid pain receptors (TRPV1, TRPV2, TRPV3) [7]

5HT1A receptor agonist (serotonin receptor) [6]

FAAH (–) [6, 7]

PPARγ nuclear receptor (+) [48]

Mg2+‐ATPase (−) [11]

Arylalkylamine N‐acetyltransferase (−) [44]

Indoleamine‐2,3‐dioxygenase (−) [45]

15‐lipoxygenase (−) [46]

Phospholipase A2 (+) [11]

Glutathione peroxidase (+) [47]

Glutathione reductase (+) [47]

5‐lipoxygenase (−) [46]

Metabolism

CYP1A1 (−) [40]

CYP1A2 & CYP1B1 (−) [40]

CYP2B6 (−) [41]

CYP2D6 (−) [42]

CYP3A5 (−) [43]

Enter KATS15 for a 15% Discount

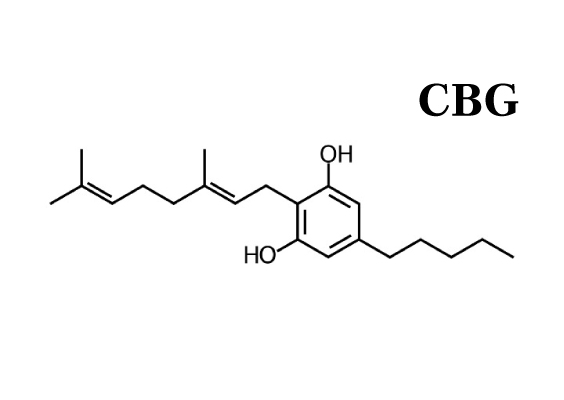

3. CBG

Cannabigerol

CBG is an early precursor for many of the other cannabinoids including THC.

Plants harvested early will be high in this compound.

Many users report that strains high in CBG are less likely to cause anxiety, and are good for people experiencing acute stress.

This is likely due to its role in blocking the serotonergic effects of THC through the 5-HT1A serotonin receptors [9].

CBG Medicinal Actions

Anti-anxiety

Adaptogenic

Mild sedative

Receptors Affected

4. CBN

Cannabinol

CBN is made from THC. As THC content breaks down with time, or heat, CBN levels increase overall.

Older harvested plants that have gone past their window of ripeness will be much higher in CBN.

It’s mostly non-psychoactive but may have some mild psychoactivity in some people.

Products or strains high in CBN will produce more of a heavy feeling and are best used for treating conditions like insomnia or anxiety.

This cannabinoid is potentially the most sedative of the group.

CBN Medicinal Actions

Sedative

Anti-anxiety

Appetite stimulant

Receptors Affected

CB1 receptor agonist [10].

Metabolism

CYP2C9

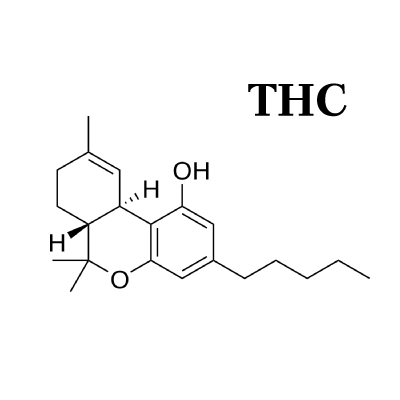

5. THC

Tetrahydrocannabinol

THC is the main psychoactive compound in the cannabis plant.

There are two main types:

Delta-8-THC — contained in very small amounts

Delta-9-THC — the most abundant form of THC in the cannabis plant

THC activates both CB1 and CB2 endocannabinoid receptors, causing changes in neurotransmitters like dopamine, norepinephrine, and most importantly, serotonin. It’s this change in neurotransmitter levels that produce the bulk of the high experienced by this compound.

Aside from its psychoactive effects, THC has medicinal benefits of its own.

It’s mentally stimulating and has some potent antidepressant effects through its euphoric effects.

THC Medicinal Actions

Appetite stimulant

Sedative (low doses)

Stimulant (high doses)

Receptors Affected

Metabolism

CYP2C9

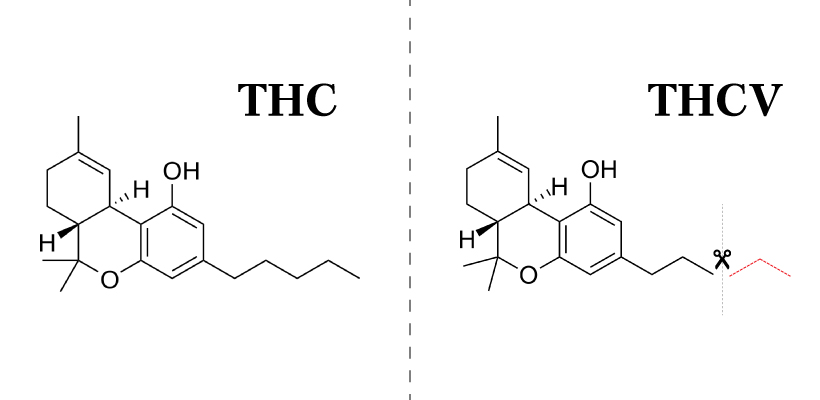

6. THCV

Tetrahydrocannabivarin

THCV is the fraternal twin of THC.

It’s virtually identical except for one slight chemical difference — THCV is missing two carbon atoms.

This makes the effects of THCV very similar to THC — but is much weaker in its effects.

One study reported THCV as being 20-25% as strong as THC in its psychoactive effects [12].

There are others affected by this, including CBCV, and CBDV, though they are in far less concentrations.

THCV Medicinal Actions

Appetite suppressant

Euphoric

Antispasmodic

Paranoic

Receptors Affected

Vanilloid receptor agonist (TRPV3 and TRPV4) [13].

7. Other Cannabinoids

There are also a lot of cannabinoids that can be found in much lower concentrations.

These make up the bottom 5% of the cannabinoid profile.

Few of these cannabinoids have many studies on them aside from chemical mapping to identify their structure.

We may see more research on these cannabinoids in the near future.

Some Novel Cannabinoids Include:

CBCV (cannabichromevarin)

CBDV (cannabidivarin)

CBE (cannabielsoin)

CBGM (cannabigerol monomethyl ether)

CBGV (cannabigerovarin)

CBL (cannabicyclol)

CBT (cannabicitran)

CBV (cannabivarin)

A Note On Synthetic Cannabinoids

There are also synthetic cannabinoids. These are compounds that are similar in shape and function to cannabinoids produced in our bodies, or in the cannabis plant.

It’s recommended that you stay far away from the synthetic cannabinoids — not only do they lack many of the medicinal actions of cannabis, they have the potential to cause serious harm.

The street drug known as “spice” is a combination of various synthetic cannabinoids. They were designed as an attempt to circumvent the legal hurdles preventing the sale of cannabis products for recreational use — and have since become a major cause of addiction and abuse.

+ Side-Effects of Synthetic Cannabinoid Use

- Agitation and anxiety

- Blurred vision

- Chest pain

- Death

- Hallucinations

- Heart attack

- High blood pressure

- Kidney failure

- Nausea and vomiting

- Paranoia

- Psychosis

- Racing heart

- Seizures

- Shortness of breath

+ List of Synthetic Cannabinoids

- JWH-018

- JWH-073

- JWH-200

- AM-2201

- UR-144

- XLR-11

- AKB4

- Cannabicyclohexanol

- AB-CHMINACA

- AB-PINACA

- AB-FUBINACA

Cannabis Terpenes

Terpenes are a class of compounds characterized by their volatile nature, and hydrocarbon-based structure. These are contained in high amounts in the essential oil of plants.

Terpenes have a very low molecular weight, and will evaporate under low temperatures. This, combined with their characteristic aromas is what gives many plants their scent. Conifer trees, fruits, and many flowers (including cannabis) all owe their aroma to their terpene profile.

Each plant can contains hundreds of different terpenes — many of which will even overlap into unrelated plant species. Cannabis shares terpenes with pine trees, many different flowers, citrus fruits, and nutmeg, among others.

Terpenes add flavor as well as additional medicinal benefits. Terpenes often have antibacterial, antiviral, antinflammatory, and anxiolytic effects.

+ List of Cannabis Terpenes

- A-humulene

- a-Terpenine

- Alpha Bisabolol

- alpha-Terpineol

- Alpha/Beta Pinene

- Beta-Caryophyllene

- Bisabolol

- Borneol

- Camphene

- Caryophyllene oxide

- D-Linalool

- Eucalyptol (1, 8 cineole)

- Geraniol

- Guaiol

- Isopulegol

- Limonene

- Myrecene

- Nerolidol

- p-Cymene

- Phytol

- Pulegone

- Terpineol-4-ol

- Terpinolene

- Trans Ocimene

- Valencene

- ∆-3-carene

Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics

Cannabinoids work by mimicking the endocannabinoids anandamide and 2-AG.

Learn more about cannabinoid metabolism.

Clinical Applications of Cannabis

As an herb, cannabis is very useful. It works through a set of receptors most other plants don’t interact with — the endocannabinoid system.

The endocannabinoid system plays a major role in maintaining homeostasis. This gives cannabis an effect profile similar to adaptogens — but through different mechanisms.

Cannabis is similar to adaptogens in that it offers a bidirectional effect profile — which means it can both increase, and decrease tissue function according to its homeostatic baseline.

But cannabis isn’t quite an adaptogen because it can’t increase the bodies resistance to stress, and doesn’t appear to exert any action on the hypothalamus or adrenal glands directly.

Although cannabis has broad actions and therefore can provide benefit to a wide range of body systems — choosing the right product, strain, and phenotype for the job is critical.

An experienced herbalist or naturopath using cannabis will take into account the cannabinoid profile, terpene content, and anecdotal effects of each strain or CBD product being used.

Unlike other herbs, you have to be very particular about the type of cannabis being used for each condition.

What Constitutes “Medicinal” Cannabis?

There’s a big difference between using cannabis because “it’s healthy”, and using it as a therapeutic agent aimed at treating a specific disease process.

Although it can be used as both, daily supplementing cannabis or extracts like CBD don’t constitute medical cannabis.

However, you can use cannabis to address the symptoms, or underlying causes for some conditions.

Cautions:

Caution advised whenever using cannabis due to the potential for intoxicating side-effects. Without careful consideration of cannabinoid profile, some strains, or cannabis products may make symptoms for certain conditions worse — especially anxiety, psychosis, bipolar disorder, and insomnia.

Recent Blog Posts:

References:

Sharma P, Murthy P, Bharath M.M.S. (2012). Chemistry, Metabolism, and Toxicology of Cannabis: Clinical Implications. Iran J Psychiatry 2012; 7:4: 149-156

Aizpurua-Olaizola, O., Soydaner, U., Öztürk, E., Schibano, D., Simsir, Y., Navarro, P., ... & Usobiaga, A. (2016). Evolution of the cannabinoid and terpene content during the growth of Cannabis sativa plants from different chemotypes. Journal of natural products, 79(2), 324-331.

Shevyrin, V. A., & Morzherin, Y. Y. (2015). Cannabinoids: structures, effects, and classification. Russian Chemical Bulletin, 64(6), 1249-1266.

De Petrocellis, L., Orlando, P., Moriello, A. S., Aviello, G., Stott, C., Izzo, A. A., & Di Marzo, V. (2012). Cannabinoid actions at TRPV channels: effects on TRPV3 and TRPV4 and their potential relevance to gastrointestinal inflammation. Acta physiologica, 204(2), 255-266.

De Meijer, E. P. M., Hammond, K. M., & Micheler, M. (2009). The inheritance of chemical phenotype in Cannabis sativa L.(III): variation in cannabichromene proportion. Euphytica, 165(2), 293-311.

Nelson, K., Walsh, D., Deeter, P., & Sheehan, F. (1994). A phase II study of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol for appetite stimulation in cancer-associated anorexia. Journal of palliative care.

Bisogno, T., Hanuš, L., De Petrocellis, L., Tchilibon, S., Ponde, D. E., Brandi, I., ... & Di Marzo, V. (2001). Molecular targets for cannabidiol and its synthetic analogues: effect on vanilloid VR1 receptors and on the cellular uptake and enzymatic hydrolysis of anandamide. British journal of pharmacology, 134(4), 845-852.

De Petrocellis, L., Vellani, V., Schiano-Moriello, A., Marini, P., Magherini, P. C., Orlando, P., & Di Marzo, V. (2008). Plant-derived cannabinoids modulate the activity of transient receptor potential channels of ankyrin type-1 and melastatin type-8. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 325(3), 1007-1015.

Cascio, M. G., Gauson, L. A., Stevenson, L. A., Ross, R. A., & Pertwee, R. G. (2010). Evidence that the plant cannabinoid cannabigerol is a highly potent α2‐adrenoceptor agonist and moderately potent 5HT1A receptor antagonist. British journal of pharmacology, 159(1), 129-141.