Sharma P, Murthy P, Bharath M.M.S. (2012). Chemistry, Metabolism, and Toxicology of Cannabis: Clinical Implications. Iran J Psychiatry 2012; 7:4: 149-156

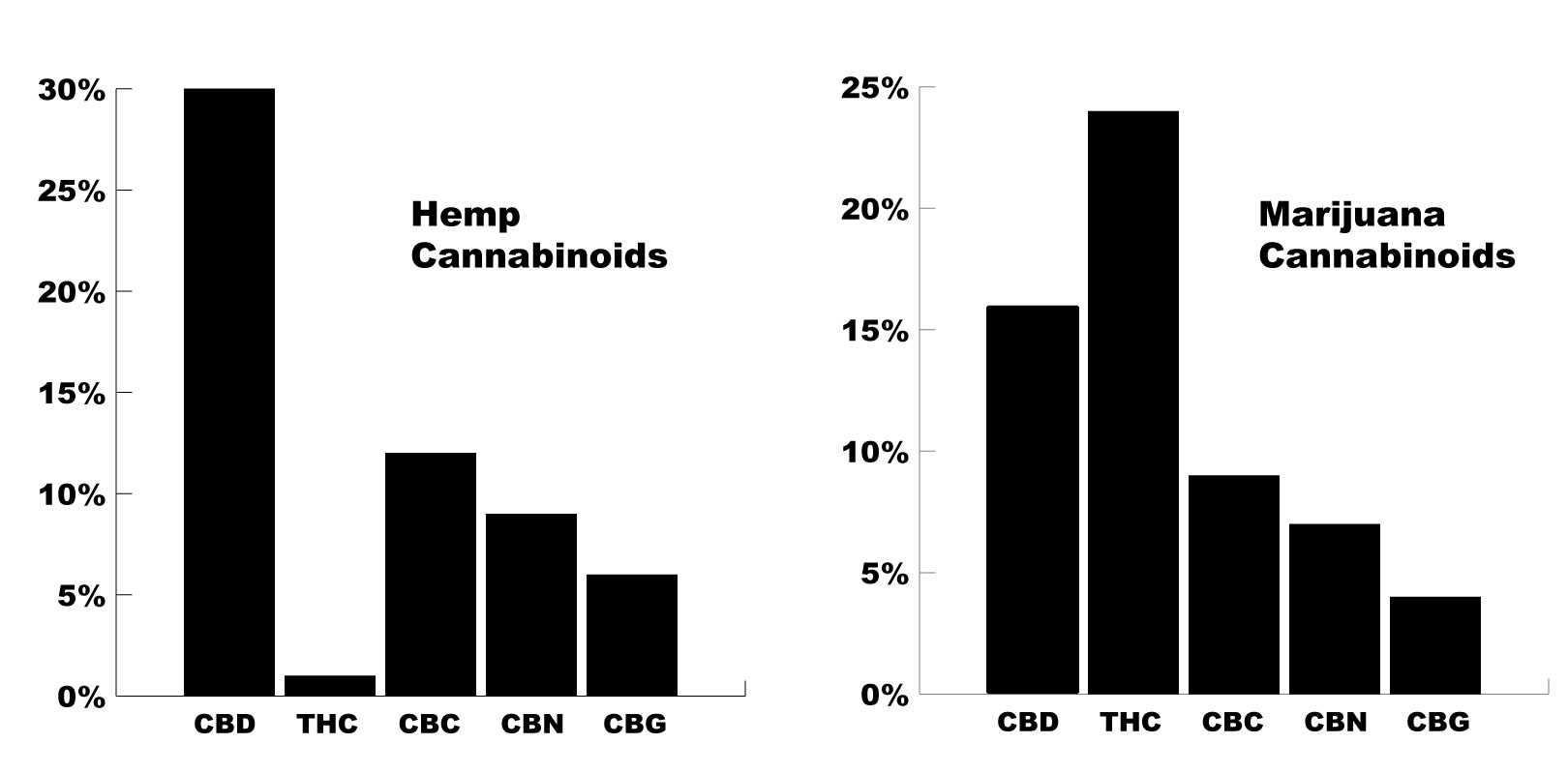

Aizpurua-Olaizola, O., Soydaner, U., Öztürk, E., Schibano, D., Simsir, Y., Navarro, P., ... & Usobiaga, A. (2016). Evolution of the cannabinoid and terpene content during the growth of Cannabis sativa plants from different chemotypes. Journal of natural products, 79(2), 324-331.

Shevyrin, V. A., & Morzherin, Y. Y. (2015). Cannabinoids: structures, effects, and classification. Russian Chemical Bulletin, 64(6), 1249-1266.

De Petrocellis, L., Orlando, P., Moriello, A. S., Aviello, G., Stott, C., Izzo, A. A., & Di Marzo, V. (2012). Cannabinoid actions at TRPV channels: effects on TRPV3 and TRPV4 and their potential relevance to gastrointestinal inflammation. Acta physiologica, 204(2), 255-266.

De Meijer, E. P. M., Hammond, K. M., & Micheler, M. (2009). The inheritance of chemical phenotype in Cannabis sativa L.(III): variation in cannabichromene proportion. Euphytica, 165(2), 293-311.

Nelson, K., Walsh, D., Deeter, P., & Sheehan, F. (1994). A phase II study of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol for appetite stimulation in cancer-associated anorexia. Journal of palliative care.

Bisogno, T., Hanuš, L., De Petrocellis, L., Tchilibon, S., Ponde, D. E., Brandi, I., ... & Di Marzo, V. (2001). Molecular targets for cannabidiol and its synthetic analogues: effect on vanilloid VR1 receptors and on the cellular uptake and enzymatic hydrolysis of anandamide. British journal of pharmacology, 134(4), 845-852.

De Petrocellis, L., Vellani, V., Schiano-Moriello, A., Marini, P., Magherini, P. C., Orlando, P., & Di Marzo, V. (2008). Plant-derived cannabinoids modulate the activity of transient receptor potential channels of ankyrin type-1 and melastatin type-8. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 325(3), 1007-1015.

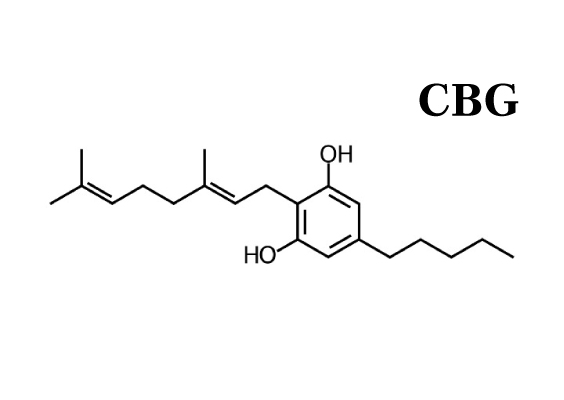

Cascio, M. G., Gauson, L. A., Stevenson, L. A., Ross, R. A., & Pertwee, R. G. (2010). Evidence that the plant cannabinoid cannabigerol is a highly potent α2‐adrenoceptor agonist and moderately potent 5HT1A receptor antagonist. British journal of pharmacology, 159(1), 129-141.

Farrimond, J. A., Whalley, B. J., & Williams, C. M. (2012). Cannabinol and cannabidiol exert opposing effects on rat feeding patterns. Psychopharmacology, 223(1), 117-129.

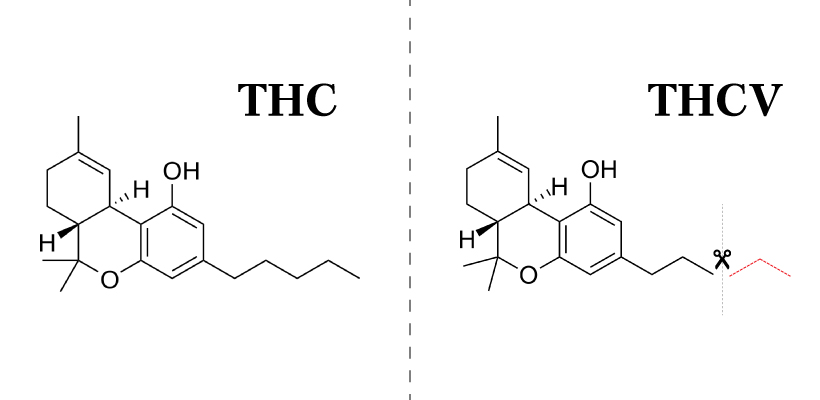

Pertwee, R. G. (2008). The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and Δ9‐tetrahydrocannabivarin. British journal of pharmacology, 153(2), 199-215.

Hollister, L. E. (1974). Structure-activity relationships in man of cannabis constituents, and homologs and metabolites of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Pharmacology, 11(1), 3-11.

Pertwee, R. G. (2006). The pharmacology of cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: an overview. International journal of obesity, 30(S1), S13.

Compton, D. R., Rice, K. C., De Costa, B. R., Razdan, R. K., Melvin, L. S., Johnson, M. R., & Martin, B. R. (1993). Cannabinoid structure-activity relationships: correlation of receptor binding and in vivo activities. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 265(1), 218-226.

Burstein, S. (2005). PPAR-γ: a nuclear receptor with affinity for cannabinoids. Life sciences, 77(14), 1674-1684.García-Arencibia, M., González, S., de Lago, E., Ramos, J. A., Mechoulam, R., & Fernández-Ruiz, J. (2007). Evaluation of the neuroprotective effect of cannabinoids in a rat model of Parkinson's disease: importance of antioxidant and cannabinoid receptor-independent properties. Brain research, 1134, 162-170.

Martín-Moreno, A. M., Reigada, D., Ramírez, B. G., Mechoulam, R., Innamorato, N., Cuadrado, A., & de Ceballos, M. L. (2011). Cannabidiol and other cannabinoids reduce microglial activation in vitro and in vivo: relevance to Alzheimers′ disease. Molecular pharmacology, mol-111.

Dirikoc, S., Priola, S. A., Marella, M., Zsürger, N., & Chabry, J. (2007). Nonpsychoactive cannabidiol prevents prion accumulation and protects neurons against prion toxicity. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(36), 9537-9544.

Malfait, A. M., Gallily, R., Sumariwalla, P. F., Malik, A. S., Andreakos, E., Mechoulam, R., & Feldmann, M. (2000). The nonpsychoactive cannabis constituent cannabidiol is an oral anti-arthritic therapeutic in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(17), 9561-9566.

Specter, S., Lancz, G., & Hazelden, J. (1990). Marijuana and immunity: tetrahydrocannabinol mediated inhibition of lymphocyte blastogenesis. International journal of immunopharmacology, 12(3), 261-267.

Klein, T. W., Kawakami, Y., Newton, C., & Friedman, H. (1991). Marijuana components suppress induction and cytolytic function of murine cytotoxic T cells in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A Current Issues, 32(4), 465-477.

McCoy, K. L., Gainey, D., & Cabral, G. A. (1995). delta 9-Tetrahydrocannabinol modulates antigen processing by macrophages. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 273(3), 1216-1223.

Coffey, R. G., Yamamoto, Y., Snella, E., & Pross, S. (1996). Tetrahydrocannabinol inhibition of macrophage nitric oxide production. Biochemical pharmacology, 52(5), 743-751.

Formukong, E. A., Evans, A. T., & Evans, F. J. (1988). Analgesic and antiinflammatory activity of constituents ofCannabis sativa L. Inflammation, 12(4), 361-371.

Watzl, B., Scuderi, P., & Watson, R. R. (1991). Marijuana components stimulate human peripheral blood mononuclear cell secretion of interferon-gamma and suppress interleukin-1 alpha in vitro. International journal of immunopharmacology, 13(8), 1091-1097.

Srivastava, M. D., Srivastava, B. I. S., & Brouhard, B. (1998). Δ9 tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol alter cytokine production by human immune cells. Immunopharmacology, 40(3), 179-185.

Pan, H., Mukhopadhyay, P., Rajesh, M., Patel, V., Mukhopadhyay, B., Gao, B., ... & Pacher, P. (2009). Cannabidiol attenuates cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by decreasing oxidative/nitrosative stress, inflammation, and cell death. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 328(3), 708-714.

Mecha, M., Feliú, A., Iñigo, P. M., Mestre, L., Carrillo-Salinas, F. J., & Guaza, C. (2013). Cannabidiol provides long-lasting protection against the deleterious effects of inflammation in a viral model of multiple sclerosis: a role for A2A receptors. Neurobiology of disease, 59, 141-150.

Notcutt, W., Langford, R., Davies, P., Ratcliffe, S., & Potts, R. (2012). A placebo-controlled, parallel-group, randomized withdrawal study of subjects with symptoms of spasticity due to multiple sclerosis who are receiving long-term Sativex®(nabiximols). Multiple Sclerosis Journal, 18(2), 219-228.

Woerly, S., Marchand, R., & Lavallée, G. (1991). Interactions of copolymeric poly (glyceryl methacrylate)-collagen hydrogels with neural tissue: effects of structure and polar groups. Biomaterials, 12(2), 197-203.

Wade, D. T., Collin, C., Stott, C., & Duncombe, P. (2010). Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of Sativex (nabiximols), on spasticity in people with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal, 16(6), 707-714.

Brady, C. M., DasGupta, R., Dalton, C., Wiseman, O. J., Berkley, K. J., & Fowler, C. J. (2004). An open-label pilot study of cannabis-based extracts for bladder dysfunction in advanced multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal, 10(4), 425-433.

Barnes, M. P. (2006). Sativex®: clinical efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of symptoms of multiple sclerosis and neuropathic pain. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy, 7(5), 607-615.

Leung, L. (2011). Cannabis and its derivatives: review of medical use. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 24(4), 452-462.

Grotenhermen, F., & Müller-Vahl, K. (2012). The therapeutic potential of cannabis and cannabinoids. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 109(29-30), 495.

Kwiatkoski, M., Guimaraes, F. S., & Del-Bel, E. (2012). Cannabidiol-treated rats exhibited higher motor score after cryogenic spinal cord injury. Neurotoxicity research, 21(3), 271-280.

Chagas, M. H. N., Zuardi, A. W., Tumas, V., Pena-Pereira, M. A., Sobreira, E. T., Bergamaschi, M. M., ... & Crippa, J. A. S. (2014). Effects of cannabidiol in the treatment of patients with Parkinson’s disease: an exploratory double-blind trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 28(11), 1088-1098.

Iuvone, T., Esposito, G., De Filippis, D., Scuderi, C., & Steardo, L. (2009). Cannabidiol: a promising drug for neurodegenerative disorders?. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics, 15(1), 65-75.

Fernández‐Ruiz, J., Sagredo, O., Pazos, M. R., García, C., Pertwee, R., Mechoulam, R., & Martínez‐Orgado, J. (2013). Cannabidiol for neurodegenerative disorders: important new clinical applications for this phytocannabinoid?. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 75(2), 323-333.

Yamaori, S., Kushihara, M., Yamamoto, I., & Watanabe, K. (2010). Characterization of major phytocannabinoids, cannabidiol and cannabinol, as isoform-selective and potent inhibitors of human CYP1 enzymes. Biochemical pharmacology, 79(11), 1691-1698.

Yamaori, S., Maeda, C., Yamamoto, I., & Watanabe, K. (2011). Differential inhibition of human cytochrome P450 2A6 and 2B6 by major phytocannabinoids. Forensic Toxicology, 29(2), 117-124.

Yamaori, S., Okamoto, Y., Yamamoto, I., & Watanabe, K. (2011). Cannabidiol, a major phytocannabinoid, as a potent atypical inhibitor for cytochrome P450 2D6. Drug Metabolism and Disposition, dmd-111.

Yamaori, S., Ebisawa, J., Okushima, Y., Yamamoto, I., & Watanabe, K. (2011). Potent inhibition of human cytochrome P450 3A isoforms by cannabidiol: role of phenolic hydroxyl groups in the resorcinol moiety. Life sciences, 88(15-16), 730-736.

Yamaori, S., Ebisawa, J., Okushima, Y., Yamamoto, I., & Watanabe, K. (2011). Potent inhibition of human cytochrome P450 3A isoforms by cannabidiol: role of phenolic hydroxyl groups in the resorcinol moiety. Life sciences, 88(15-16), 730-736.

Koch, M., Dehghani, F., Habazettl, I., Schomerus, C., & Korf, H. W. (2006). Cannabinoids attenuate norepinephrine‐induced melatonin biosynthesis in the rat pineal gland by reducing arylalkylamine N‐acetyltransferase activity without involvement of cannabinoid receptors. Journal of neurochemistry, 98(1), 267-278.

Jenny, M., Santer, E., Pirich, E., Schennach, H., & Fuchs, D. (2009). Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol modulate mitogen-induced tryptophan degradation and neopterin formation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. Journal of neuroimmunology, 207(1-2), 75-82.

Takeda, S., Usami, N., Yamamoto, I., & Watanabe, K. (2009). Cannabidiol-2', 6'-dimethyl ether, a cannabidiol derivative, is a highly potent and selective 15-lipoxygenase inhibitor. Drug Metabolism and Disposition.

Usami, N., Yamamoto, I., & Watanabe, K. (2008). Generation of reactive oxygen species during mouse hepatic microsomal metabolism of cannabidiol and cannabidiol hydroxy-quinone. Life sciences, 83(21-22), 717-724.

Pertwee, R. G., Howlett, A. C., Abood, M. E., Alexander, S. P. H., Di Marzo, V., Elphick, M. R., ... & Mechoulam, R. (2010). International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: beyond CB1 and CB2. Pharmacological reviews, 62(4), 588-631.

As COVID-19 continues to spread around the world, we’re getting a lot of questions on what the potential role of herbal medicine is during the outbreak. Learn how the virus works and how to limit your chances of transmission.